In this article, I briefly describe how genetic predisposition and environmental exposures interact to drive the development of Type I hypersensitivity (allergic) diseases. Type I hypersensitivity, commonly known as allergy, is an IgE-driven immune disorder characterized by exaggerated responses to otherwise harmless environmental antigens. Its development is influenced by a complex interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors that shape immune regulation from early life.

Type I Hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity reactions represent exaggerated immune responses mediated through humoral or cell-mediated pathways. It often results in tissue injury and, in severe cases, mortality. Based on the kinetics of the immune response and clinical manifestation, hypersensitivity reactions are broadly classified as immediate or delayed.

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate, IgE-mediated immune response commonly associated with allergic disorders. It is initiated by exposure to specific antigens, termed allergens, and may manifest as either localized or systemic reactions. Clinically, Type I hypersensitivity affects multiple organ systems, including the skin (urticaria and eczema), eyes (conjunctivitis), upper respiratory tract (rhinitis), lower respiratory tract (asthma), and gastrointestinal tract (gastroenteritis).

At the molecular level, allergen exposure induces activation of T helper 2 (TH2) cells, leading to the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) by plasma cells. IgE antibodies bind with high affinity to FcεRI receptors on mast cells and basophils, resulting in cellular sensitization. Subsequent re-exposure to the same allergen causes cross-linking of receptor-bound IgE, triggering mast cell and basophil degranulation and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators that drive the clinical features of Type I hypersensitivity.

Environmental Determinants of Allergic Susceptibility

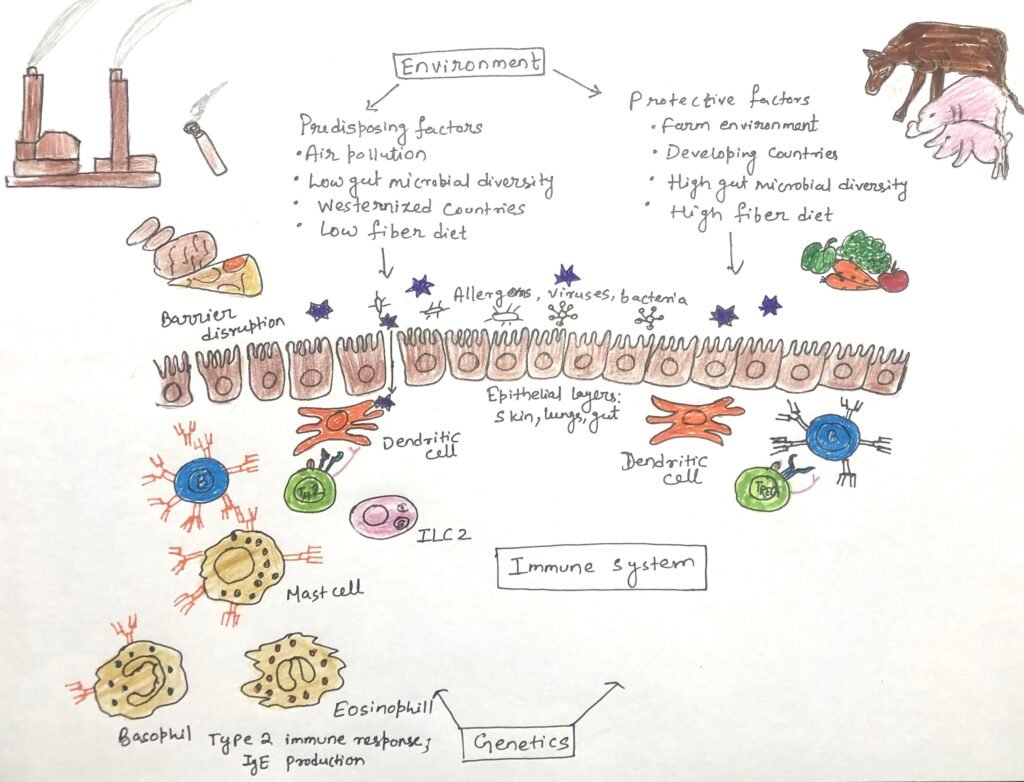

The likelihood of developing allergies is shaped by multiple aspects of our environment. These include external exposures such as air pollution, internal factors like the foods we consume, and the microorganisms we encounter (Figure 1). Together, these environmental elements play a significant role in influencing allergic susceptibility.

Role of Air Pollution in Triggering Atopic Dermatitis and Allergic Disease

Certain air pollutants, such as industrial smoke and diesel exhaust, have been strongly linked to the development of allergic conditions. Exposure to these pollutants is particularly associated with early-onset atopic dermatitis, which can later progress to asthma. Recent research has clarified how polluted air contributes to the development of atopic dermatitis. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), key organic components of airborne particulate matter, can pass through the outermost layer of the skin and activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) present on keratinocytes.

Once activated, these cells release mediators that enhance hypersensitivity and provoke itching. Persistent itching and scratching, along with these inflammatory responses, compromise the skin’s epithelial barrier, facilitating the entry of additional allergens and promoting the onset of atopic dermatitis. Furthermore, AhR activation induces the expression of cytokines such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and interleukin-33 (IL-33), both of which amplify local allergic inflammation.

Environmental tobacco smoke is another form of air pollution. Early-life exposure to passive smoking increases the risk of asthma and may also contribute to the development of eczema.

Protective Role of Farm Exposure and Microbial Diversity in Allergy Prevention

Studies show that regular contact with farm animals and the microorganisms they carry reduces the risk of developing allergic diseases such as hay fever, atopic dermatitis, and asthma.

Population-based comparisons conducted across Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States demonstrate that children raised in proximity to livestock are significantly less likely to develop asthma during childhood.

More broadly, a rich and diverse gut microbiome appears to play a crucial role in safeguarding against type I hypersensitivity reactions. Beneficial intestinal microbes are essential for maintaining immune balance and for establishing tolerance to dietary antigens. In contrast, widespread and early use of antibiotics, particularly common in industrialized societies, can disrupt normal microbial communities, thereby increasing vulnerability to allergic disorders. Research indicates that antibiotic use during the first year of life is linked to a higher incidence of food allergies in young children. On the other hand, probiotic supplementation may help counteract this risk, with several studies suggesting that probiotics can lower the likelihood of developing allergic conditions, especially eczema, in children.

Influence of Early-Life Nutrition on Allergic Susceptibility

Nutritional exposures before birth and during early childhood represent a major environmental factor shaping the risk of developing allergic diseases, although the underlying mechanisms are highly intricate. The dietary habits of a pregnant woman can influence the immune programming of the fetus, thereby affecting the newborn’s tendency toward allergies. Additionally, several studies suggest that breastfeeding provides protective benefits by lowering the likelihood of allergic outcomes in infancy.

Diets rich in plant-derived fiber from fruits and vegetables, which people consume more frequently in developing regions than in industrialized countries, reduce the incidence of childhood asthma and allergic disorders.Dietary fiber promotes a diverse gut microbiota, including beneficial commensal organisms that are capable of fermenting fiber into short-chain fatty acids, such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate. These metabolites act on intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells, stimulating the production of regulatory molecules like interleukin-10 (IL-10), which suppress type 2 immune pathways driven by TH2 cells and group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s). Since cytokines released by these cells enhance IgE synthesis and allergic inflammation, their inhibition contributes to protection against allergy development.

Evidence further underscores the relationship between diet and allergic risk by showing that different classes of dietary fats exert distinct effects on allergic outcomes. Moreover, vitamins traditionally known to enhance immune function, such as vitamins A and D, have produced inconsistent results in allergy prevention, highlighting the complex and multifaceted role of nutrition in modulating allergic predisposition.

Role of The Hygiene Hypothesis in Allergic Disease

Early observations described type I hypersensitivity disorders as more common in Western industrialized societies and less frequent in environments with greater early-life microbial exposure, as seen in many developing regions. These findings gave rise to the hygiene hypothesis, which proposes that exposure to certain microbes during infancy and early childhood helps shape the immune system in ways that reduce the risk of allergies.

At birth, the immune system naturally favors type 2 (TH2) responses that promote IgE production and allergic reactions. In non-allergic children, this TH2 bias normally decreases during early childhood. In contrast, allergic children tend to retain or strengthen this bias. Exposure to common childhood infections appears to redirect immune responses away from TH2 pathways, either by promoting TH1 responses or through regulatory T cells (TREGs) that suppress TH2 activity.

In highly westernized societies, improved sanitation, widespread vaccination, antibiotic use, and reduced contact with animals limit early microbial exposure.

As a result, the immune system may not receive sufficient signals to shift away from TH2-dominated responses, increasing susceptibility to allergic diseases.

Genetic Factors Contributing to Allergic Susceptibility

Early evidence for a genetic contribution to allergic disease emerged from a study conducted in 1916, which reported that nearly half (48%) of individuals with allergies had a family history of allergic conditions, compared with only 14% among individuals without allergies. These findings highlighted the importance of inherited factors in determining susceptibility to allergies.

Subsequent genetic studies have identified multiple loci that may predispose individuals to allergic disorders. Many of these loci encode proteins essential for preserving epithelial barrier integrity and for initiating and regulating immune responses. These include genes involved in innate immune recognition, cytokine and chemokine signaling, and their receptors, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, transcription factors, and other mediators that directly contribute to the initiation and amplification of allergic reactions.

Initiation and Progression of Food Allergies

Researchers have clarified how allergic responses are initiated by advancing the understanding of genetic and environmental determinants of allergic susceptibility and by studying evidence from both human and animal models. A key early event in this process is the breakdown of epithelial barrier integrity, which may result from inherited defects or environmental insults such as infections or air pollution. Barrier disruption permits allergens to penetrate epithelial surfaces and initiate immune sensitization.

Evidence suggests that initial sensitization to food allergens frequently occurs through the skin rather than the gut. Studies support this concept by showing that infants who develop eczema within the first few months of life have a markedly higher risk of developing food allergies, particularly to egg and peanut, during infancy. Further support comes from observations that children with inherited defects in filaggrin, a structural protein essential for maintaining the skin barrier, are more susceptible to food allergies, emphasizing the importance of transcutaneous allergen entry.

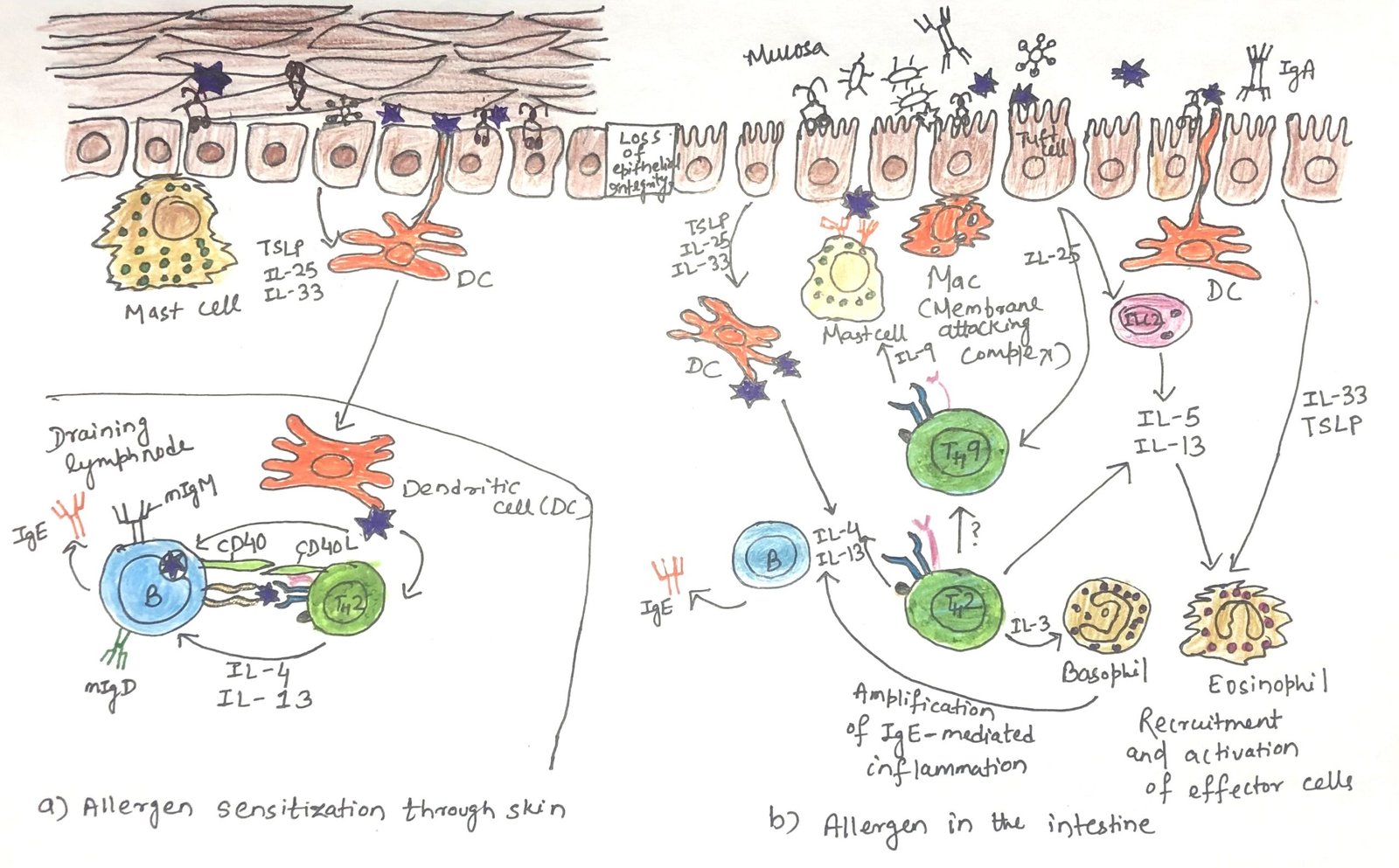

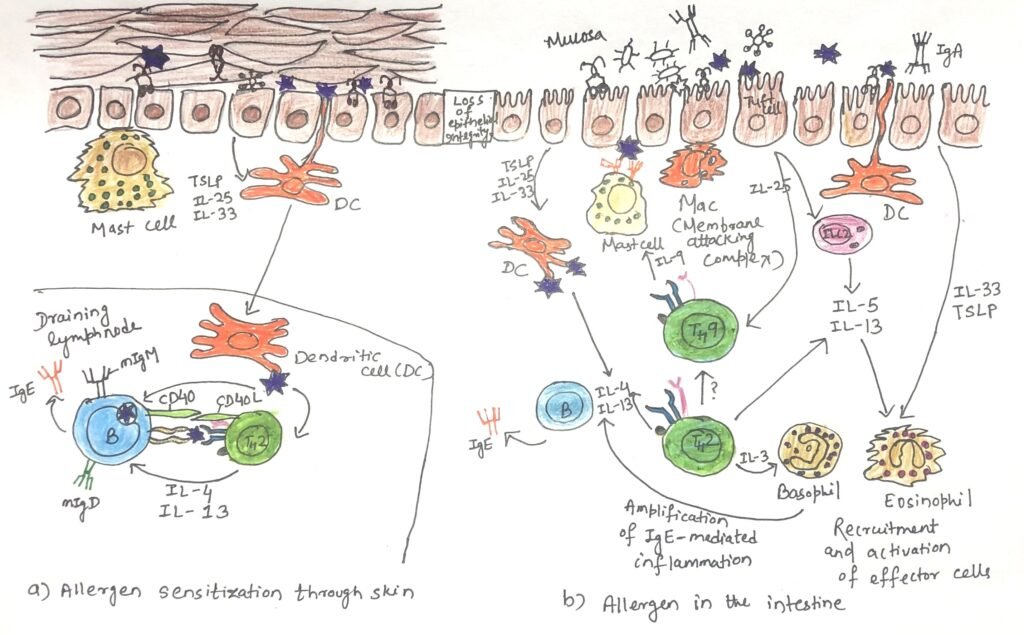

Following epithelial damage or allergen exposure, skin epithelial cells release innate cytokines, including thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), interleukin-33 (IL-33), and interleukin-25 (IL-25) (Figure 2). These cytokines act on dendritic cells to promote the differentiation of allergen-specific T helper 2 (TH2) cells. TH2-derived cytokines, particularly IL-4 and IL-13, drive B cells to undergo class switching and produce IgE antibodies. Circulating IgE subsequently localizes to mucosal tissues such as the intestine.

Within the intestinal environment, epithelial cells, innate lymphoid cells type 2 (ILC2s), and TH2-related T cell subsets secrete cytokines that recruit and activate mast cells and basophils. Cross-linking of IgE on these cells by allergen exposure triggers degranulation and release of inflammatory mediators, resulting in the clinical manifestations of food allergy, including gastrointestinal symptoms and, in severe cases, anaphylaxis.

Conclusion

Type I hypersensitivity, commonly referred to as allergy, arises from a complex interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures. Disruption of epithelial barriers, early-life encounters with allergens, air pollutants, dietary factors, and microbial environments all critically shape immune development and allergic susceptibility. Genetic variations affecting barrier integrity and immune regulation further modulate the risk of allergic sensitization. Together, these factors promote IgE-driven immune responses that lead to the clinical manifestations of allergic disease. A clearer understanding of how genetic and environmental influences converge to drive Type I hypersensitivity not only explains the rising prevalence of allergies but also highlights potential strategies for prevention and early intervention.

You may also like:

- Type-I Hypersensitive Reaction

- Intestinal immunity can initiate both type 1 and type 2 immune responses

- Type-II hypersensitivity

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.