In this article, I briefly explain the biochemical and physical characterization of bacteria present in milk. Milk provides an excellent environment for the growth of diverse bacterial populations. The biochemical and physiological characterization of bacteria present in milk is therefore essential for understanding milk quality, spoilage patterns, and safety concerns.

Microbial Association with Food and Its Impact on Milk Quality and Spoilage

Food serves as an excellent medium for the growth of microorganisms, and virtually all foods are associated with microbial populations in one way or another. These microorganisms can significantly influence the quality, availability, safety, and shelf life of food. Fresh fruits and vegetables naturally harbor microorganisms and may acquire additional contamination during harvesting, handling, and storage. Uncontrolled microbial growth leads to food decomposition and spoilage, resulting in economic losses and potential health risks.

Milk, being a nutrient-rich food, is particularly susceptible to microbial contamination. Microorganisms present in milk are mechanically flushed out from the teat canal during milking. The microbial count at the time of milking has been reported to range from several hundred to several thousand bacteria per milliliter. These counts may vary among different cows, among the quarters of the same cow, and are typically highest during the initial stages of milking.

From the moment milk leaves the udder until collection and storage, it can encounter additional sources of contamination. These sources include environmental air, milking equipment, storage containers, and personnel handling the milk. In the absence of proper sanitary practices during milking and handling, milk becomes heavily contaminated. This milk deteriorates rapidly. In contrast, milking conducted under strict hygienic conditions yields milk with low bacterial counts and improved keeping quality.

Biochemical Characteristics of Milk Bacteria

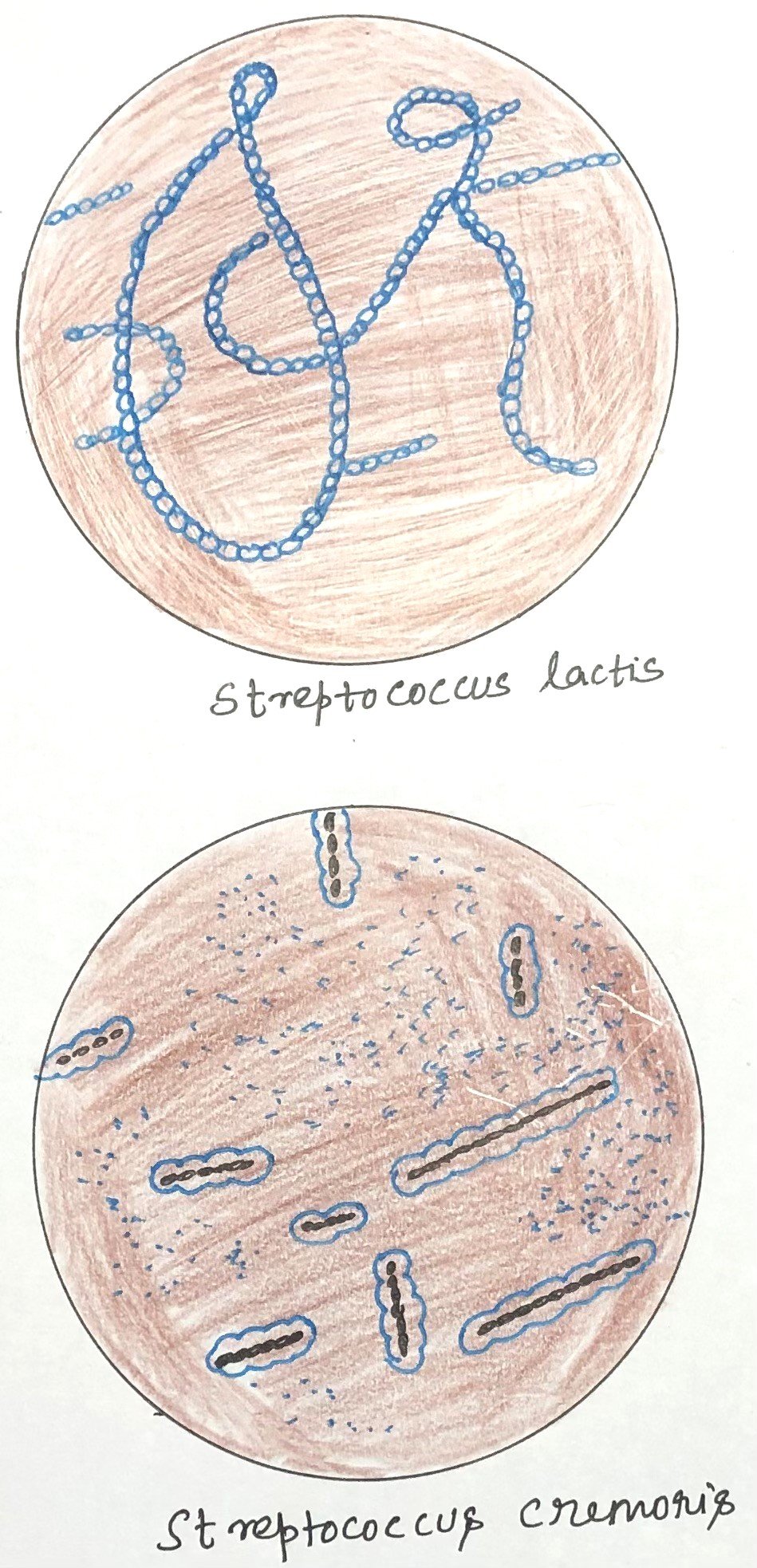

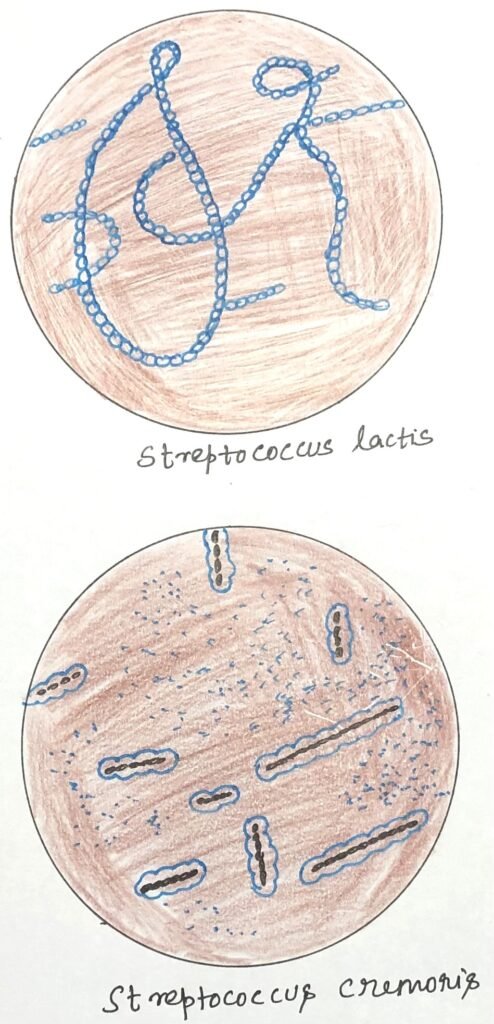

Raw milk of good sanitary quality, stored under conditions favorable for bacterial growth, typically develops a pleasant sour taste. Lactic acid–producing bacteria, particularly Streptococcus lactis, Streptococcus cremoris, and certain species of Lactobacillus, mainly cause this transformation. (Figure 1).

The primary biochemical change involved is the fermentation of lactose into lactic acid. During this process, there is no noticeable breakdown of proteins or fats, as proteolysis and lipolysis are not evident through taste or odour. Such changes represent the normal fermentation of milk, which differs from spoilage caused by undesirable microorganisms. Some organisms produce changes beyond mere production of acid (Table 1).

Table 1

| Representative Microorganisms | Source of Microorganisms | Biochemical Type | Substrate Acted Upon and End Products | Additional Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Bacillus spp. Pseudomonas spp. Proteus spp. Streptococcus liquefaciens | Soil, water, utensils | Proteolytic | Proteolytic organisms break down casein into peptides and amino acids, often after initial coagulation by the enzyme rennin. | End products of proteolysis may impart abnormal flavor or odor to milk; Pseudomonas spp. may also cause milk discoloration. |

Pseudomonas fluorescens Achromobacter lipolyticum Candida lipolytica Penicillium spp. | Soil, water, utensils | Lipolytic | Lipolytic microorganisms hydrolyze milk fat into glycerol and fatty acids. | Certain fatty acids impart rancid odor and taste to milk. |

Lactobacillus casei L. plantarum L. brevis L. fermentum Streptococcus lactis S. cremoris | Feeds, silage, manure Dairy utensils, silage, plants | Acid Producers | Lactose is fermented to lactic acid and other products. Some species are homofermentative, while others are heterofermentative. Lactose is fermented to lactic acid and acetic acid, ethyl alcohol, and carbon dioxide | Homofermentative types produce mainly lactic acid; heterofermentative types produce a mixture of products. |

| Microbacterium lacticum | Manure, dairy utensils, and dairy products | Acid Producers | Lactose is fermented to lactic acid and other end products, though acid production is lower than in streptococci or lactobacilli. | Some strains can survive high temperatures (80–85°C for 10 minutes). |

Escherichia coli Enterobacter aerogenes | Manure, polluted water, soil, and plants | Acid Producers | Lactose is fermented to a mixture of acids, gases, and neutral products. | The presence of coliform bacteria indicates poor sanitary quality of milk. |

Micrococcus luteus M. varians | Duct of cow’s mammary glands, dairy utensils | Weak Acid Producers | Small amounts of acid are produced from lactose; organisms are also weakly proteolytic. | Moderately heat resistant; some strains survive 63°C for 30 minutes. |

Clostridium butyricum Torula cremoris | Soil, manure, water, feed | Gas Producers | Lactose fermentation with the accumulation of gases such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen. | Excess gas formation may force open the lids of bulk milk containers. |

Alcaligenes viscolactis Enterobacter aerogenes Streptococcus cremoris | Soil, water, plants, feed | Stringy Fermentation | Synthesis of viscous polysaccharides forming slime layers or capsules. | Milk promotes capsule formation; sterile skim milk is often used as a culture medium. |

Temperature-Based Classification of Bacteria in Milk

Bacteria that enter milk can be classified on the basis of their optimum growth temperature and resistance to heat. Temperature plays a crucial role in milk preservation, as low temperatures inhibit microbial activity, while high temperatures reduce microbial load, eliminate pathogenic organisms, and enhance the keeping quality of milk.

The milk bacterial population is broadly grouped into four temperature categories: psychrophilic, mesophilic, thermophilic, and thermoduric. The storage temperature of milk largely determines which of these groups survives and dominates. Psychrophilic bacteria are capable of growing at temperatures just above freezing, whereas thermophilic bacteria thrive at elevated temperatures, often exceeding 65 °C.

Refrigerated pasteurized milk can remain acceptable in quality for a week or longer. However, over time, spoilage becomes evident due to the growth of psychrophilic bacteria, which produce metabolic by-products responsible for undesirable flavors and odors. At the higher end of the temperature range, thermophilic bacteria pose a different challenge. During the pasteurization holding method, processors heat milk to 62.8 °C for 30 minutes. However, certain thermophiles, such as Bacillus stearothermophilus, grow at temperatures around 65 °C and can survive this process. Generally, processing and storage temperatures significantly influence the type of bacteria that predominate in milk (Table 2).

.

Table 2

| Holding Temperature, ℃ | Changes in Numbers | Predominant Organisms |

| 1-4 | A slow initial decline occurs during the early days, with a gradual increase evident after 7–10 days. | True psychrophiles, e.g., species of Flavobacterium, Pseudomonas, and Alcaligenes |

| 4-10 | Only minor changes in bacterial numbers occur during the initial days, followed by a rapid increase, resulting in large populations after 7–10 days. | True psychrophiles, on holding changes like ropiness, sweet curdling, proteolysis, etc., are produced. |

| 10-20 | Bacterial numbers increase very rapidly, with excessive populations being reached within a few days or even less. | Predominantly acid-producing bacteria, e.g., Lactic streptococci |

| 20-30 | High bacterial counts are reached within hours. | Lactic streptococci, coliforms, and other mesophilic types |

| 30-37 | High bacterial populations develop within hours | Coliform group favored |

| More than 37 | High bacterial populations develop within hours | True psychrophiles, on holding changes like ropiness, sweet curdling, proteolysis, etc. are produced. |

Thermoduric Bacteria in the Dairy Industry

Thermoduric bacteria are microorganisms that can withstand pasteurization but do not multiply at pasteurization temperatures. They pose a serious challenge in the dairy industry, especially when the goal is to produce raw milk with a low bacterial load. Since these bacteria survive heat treatment, they can persist on processing equipment and gradually build up if cleaning and sanitation are inadequate. As a result, milk processed later using the same equipment can become highly contaminated.

These bacteria do not belong to a single species or genus. Instead, they are present across several genera, including Microbacterium lacticum, Micrococcus luteus, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bacillus subtilis.

Transmission of Milk-Borne Pathogenic Bacteria

In recent times, milk has contributed to fewer disease outbreaks, and the public and regulatory authorities no longer consider it a major source of foodborne illness. Strict regulations and effective monitoring at every stage of production, processing, and distribution ensure the safety of milk and dairy products and establish them as exemplary foods in terms of safety control.

In addition, well-established and standardized analytical methods exist for testing dairy products. No other food group matches the level of uniform surveillance and analytical standardization applied to milk and milk products.

Despite these advances, milk still has the potential to transmit certain diseases. Pathogenic microorganisms present in milk may originate from either animals or humans, and transmission can occur in multiple directions. Possible routes of transmission include:

- From infected cows to milk to humans or other cows, such as in cases of tuberculosis, brucellosis, and mastitis.

- From infected humans or carriers to milk to other humans, leading to diseases like typhoid fever, diphtheria, dysentery, and scarlet fever.

Additionally, humans can also transmit infections to cows. Several microorganisms, including Staphylococcus aureus, cause mastitis, and in some cases, human handlers serve as the source of infection.

Conclusion

Milk provides a highly favorable environment for the growth of microorganisms. The types of bacteria present and the conditions under which handlers manage, process, and store milk largely determine the nature and extent of microbial activity. The biochemical and physiological characteristics of milk bacteria, particularly their temperature requirements and metabolic activities, play a decisive role in determining milk quality, shelf life, and safety. While proper hygiene during milking and handling minimizes initial contamination, storage temperature and heat treatment ultimately influence which bacterial groups survive and predominate. Psychrophilic bacteria are mainly responsible for spoilage during refrigerated storage, whereas thermophilic and thermoduric bacteria may withstand heat treatments and pose challenges during pasteurization. A clear understanding of these microbial characteristics is therefore essential for effective milk preservation, quality control, and the prevention of spoilage and foodborne illness.

You may also like:

- Archaebacteria and Their Unique Adaptations

- Microorganisms Develop Drug Resistance

- The Role of Temperature in Food Preservation

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.