In this article, I briefly describe the immunological mechanisms underlying graft rejection. Graft rejection is a complex immune reaction in which the recipient’s immune system identifies the transplanted tissue as foreign and mounts a defense against it. Understanding the immunological pathways underlying this response, from T-cell activation to antibody-mediated injury, is essential for improving transplant success and long-term graft survival.

Allograft Rejection

Allograft rejection refers to the immune system’s defensive reaction against a transplanted organ or tissue that comes from a genetically different individual of the same species. This response is triggered when the recipient’s immune cells identify the donor’s antigens as foreign and begin an attack against the graft. The rejection rate varies among tissues. Skin grafts are rejected more rapidly than organs like the kidney or heart. Similar to other immune challenges, allograft antigens can induce both primary and secondary immune responses. If the recipient’s immune system is encountering these antigens for the first time, the reaction develops slowly over 7–10 days. In contrast, secondary responses occur much faster, beginning within hours by antibody-mediated mechanisms and escalating over the next few days through T cell-driven processes.

Types of Graft Rejection and Their Prevention

The intensity and timing of graft rejection depend on the type of transplanted tissue and the overall condition of the recipient. Rejection can occur in several forms. Hyperacute rejection, which develops within the first 24 hours; acute rejection, which typically arises within the first few weeks; and chronic rejection, which may emerge months or even years after transplantation. Proper blood group matching, thorough tissue typing, and effective cross-matching prevent most early hyperacute reactions. Moreover, advances in modern immunosuppressive therapies have significantly improved the management of acute rejection. Thus, helping extend the survival of transplanted organs.

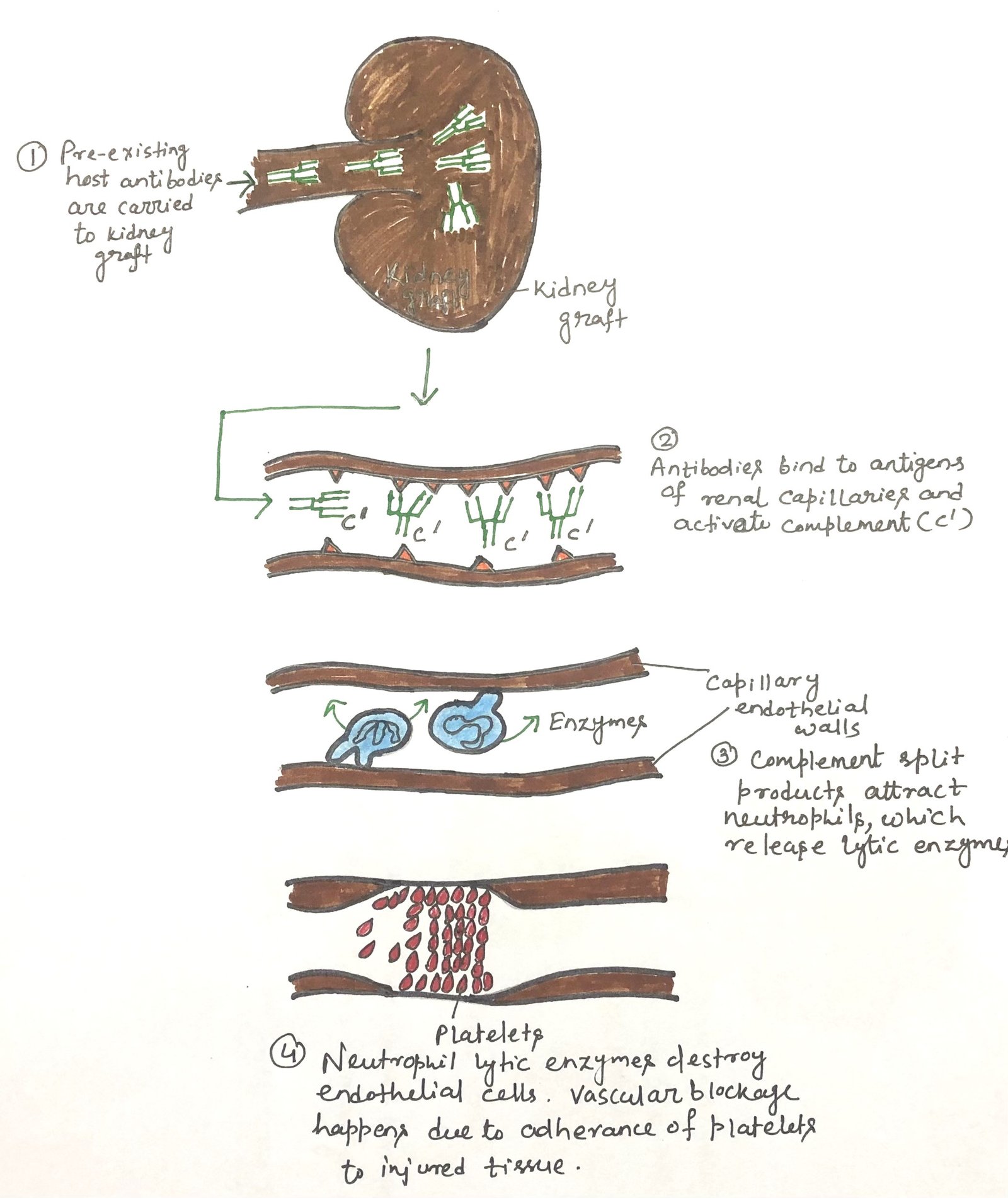

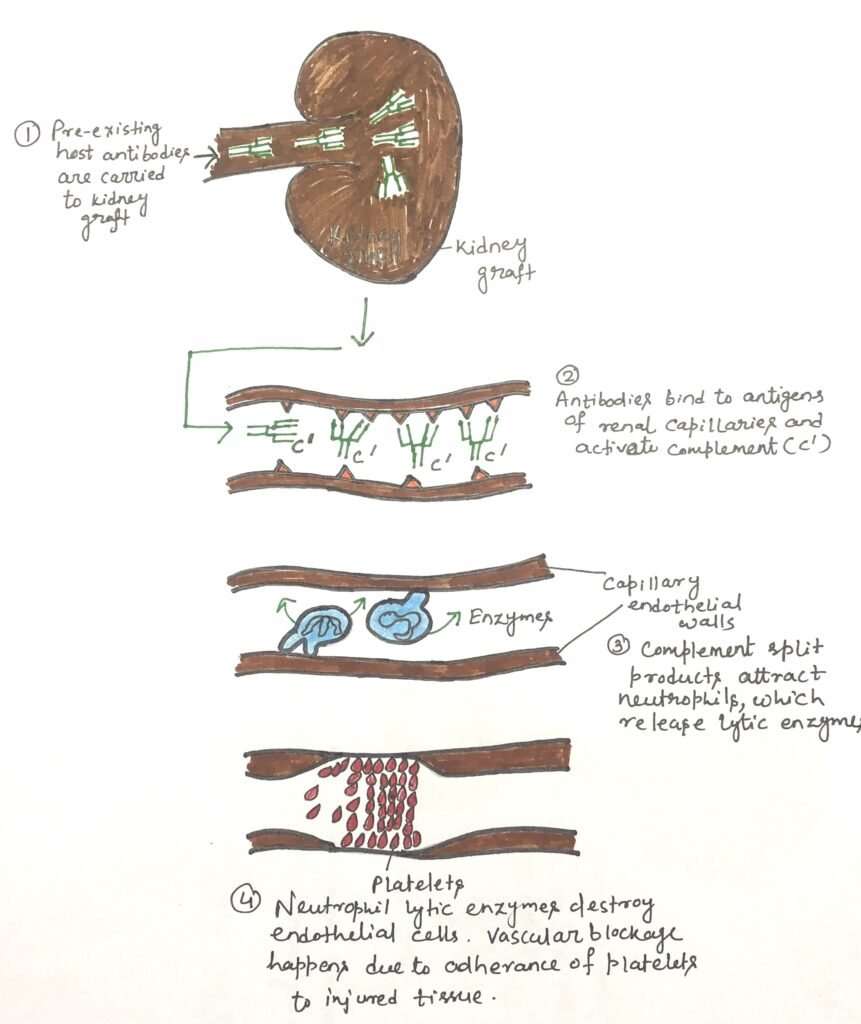

Hyperacute Rejection and Antibody-Mediated Damage

Occasionally, a transplanted organ is rejected so rapidly that it never becomes properly vascularized. This hyperacute rejection occurs when the recipient already has circulating antibodies against antigens on the donor tissue, a process known as antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). These preformed antibodies, most often targeting ABO blood group antigens or donor MHC molecules, quickly bind to endothelial cells in the graft’s blood vessels. This triggers complement activation, neutrophil accumulation, and intense inflammation, leading to endothelial injury and obstruction of the capillaries (Figure 1). Because of this vascular obstruction, the graft fails before it integrates. Although AMR is most commonly linked to hyperacute rejection, it may arise at any stage of allograft rejection.

Mechanisms Underlying Acute Graft Rejection

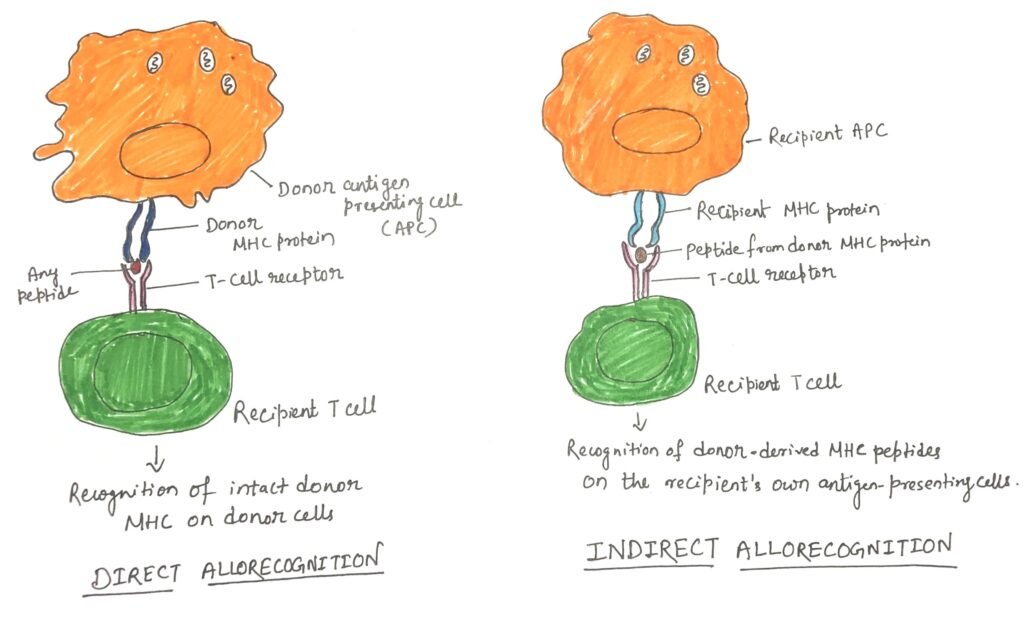

Acute rejection occurs when the recipient’s immune system attacks the transplanted organ, even without the pre-existing antibodies that would normally trigger hyperacute rejection. This process unfolds in two phases, sensitization and effector, much like classic hypersensitivity responses. In the sensitization stage, recipient CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells identify alloantigens on donor cells and begin to proliferate. These antigens may include both major and minor histocompatibility molecules. Although responses to minor antigens are individually mild, their combined effect can lead to a strong reaction. T-cell activation may occur through direct recognition of donor MHC molecules displayed on graft cells or through indirect recognition (Figure 2). In indirect recognition, recipient antigen-presenting cells process donor MHC proteins and present the resulting peptides using self-MHC molecules.

Antigen Presentation Pathways Driving Allograft Sensitization

The activation of naïve T cells depends on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that display the correct antigen, MHC combination, along with essential costimulatory signals. Donor-derived dendritic cells (DCs), which naturally express high levels of MHC class II molecules and reside in most tissues, can migrate from the graft to nearby lymph nodes and initiate direct antigen presentation. Host APCs can also enter the transplanted tissue, engulf donor major and minor histocompatibility antigens, and present them indirectly as processed peptides on self-MHC molecules. Tissue damage during transplantation releases danger signals that enhance APC activation and amplify this process. Furthermore, dendritic cells can cross-present engulfed antigens on MHC class I molecules, enabling CD8⁺ T-cell involvement in graft rejection. Other cells, such as Langerhans cells and vascular endothelial cells, which express both MHC class I and II may also contribute to antigen presentation and early immune activation during sensitization.

T cells that engage their TCR without receiving the necessary costimulatory or danger signals often become tolerant instead of activated. Introducing donor blood into a recipient before transplantation can promote acceptance of a later graft from the same donor. This effect indicates that early, non-inflammatory exposure to donor cells helps the immune system develop tolerance to donor alloantigens.

The sensitization phase develops over time. As a result, the effector stage of acute rejection usually appears 7 to 10 days after transplantation, depending on the immunosuppressive regimen. This phase is characterized by a significant accumulation of leukocytes, particularly CD4⁺ T cells and macrophages.

T Cells can Transfer Allograft Rejection

Experimental transplantation studies in animal models highlight the essential role of T cells in acute rejection. Nude mice, which lack a thymus and therefore do not produce functional T cells, are unable to reject allografts and can even accept xenografts. Additional research shows that T cells from an allograft-primed mouse can transfer a second-set rejection response to an unprimed syngeneic recipient, provided the recipient receives a graft from the same allogeneic donor.

T-Cell–Mediated Mechanisms in Acute Graft Rejection

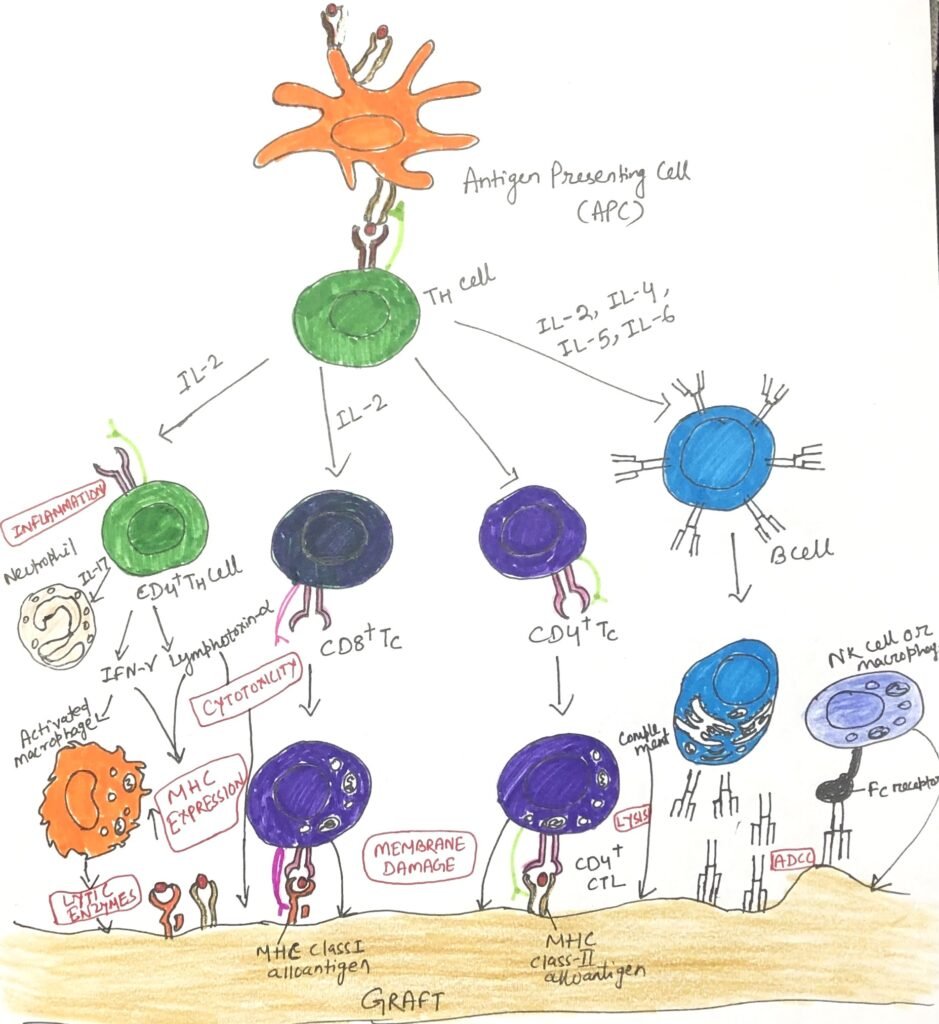

The pattern of cellular infiltration observed in acute rejection resembles that of a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, with T-cell-released cytokines orchestrating strong recruitment of inflammatory cells. Although less dominant, host CD8+ T cells can also contribute by directly recognizing donor MHC class I molecules or donor peptides cross-presented on self MHC class I, leading to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)–mediated damage.

Experimental evidence reinforces the cooperative role of both T-cell subsets. In one study, researchers used monoclonal antibodies to selectively deplete CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells in mice before performing the graft. Eliminating CD8+ T cells alone did not alter the rejection timeline (15 days), while depleting CD4+ T cells extended graft survival to about 30 days. However, when both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were removed, allografts survived for up to 60 days. These findings show that both subsets contribute to the rejection process, and their combined activity accelerates graft destruction.

Cytokine-Driven Pathways in Acute Graft Rejection

Cytokines released by TH cells are key mediators of acute graft rejection. TH1-derived IL-2 and IFN-γ are especially critical, as they stimulate T-cell expansion, enhance DTH-type inflammation, and promote B-cell production of IgG, which can activate complement. During rejection episodes, levels of cytokines such as interferons and TNFs rise, increasing the expression of MHC class I and class II molecules on various cell types and amplifying immune recognition of the graft.

Cytokines linked to TH2 and TH17 responses also contribute significantly. Increased production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6, which support B-cell activity and eosinophil infiltration, has been associated with graft injury. Elevated IL-17 levels further implicate TH17 cells, with studies showing that blocking IL-17 can prolong cardiac allograft survival in mice. Although less common, antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) still poses a major threat during acute rejection, as alloreactive B cells remain activated and sustained through T-cell-dependent signals.

The generation of various effector cells depends directly or indirectly on cytokines secreted by activated T helper cells, as shown in the figure below (Figure 3).

Chronic Rejection

Chronic graft rejection typically appears months or even years after earlier acute rejection episodes subside. Both humoral and cell-mediated immune mechanisms actively drive this process. Although modern immunosuppressive therapies and improved tissue-typing methods have significantly enhanced short-term graft survival, they are far less effective at preventing or treating long-term deterioration. As a result, chronic rejection often progresses despite medication and may eventually require a second transplant.

Evidence shows that up to 60% of patients with chronic allograft dysfunction carry donor-specific antibodies, indicating that antibody-mediated mechanisms, alongside cellular responses, play a major role. These antibodies can promote tissue injury through complement activation or through processes such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). Over time, this ongoing immune attack leads to fibrosis, vascular narrowing, and gradual loss of graft function, making chronic rejection one of the most significant challenges in long-term transplant success.

Conclusion

Graft rejection is a major challenge in transplantation and arises when the recipient’s immune system identifies the transplanted tissue as foreign. This immune reaction can occur immediately, within weeks, or even years after the procedure, depending on the type of rejection. Although careful donor–recipient matching and improved immunosuppressive therapies have reduced the frequency of severe rejection episodes, the risk is never eliminated. Understanding the mechanisms, early signs, and preventive measures is essential for improving graft survival and long-term patient outcomes. Continuous monitoring, timely treatment, and advances in immunology together play a key role in achieving successful transplantation.

You may also like:

- Pre-Transplantation Tests for Organ Transplantation

- The Basics of Organ Transplantation

- Therapeutic Approaches to Immune Suppression

- Induction of Immune Tolerance in Organ Transplantation

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.