In this article, I provide a brief description of high-density lipoproteins and reverse cholesterol transport. Cholesterol is an essential lipid required for maintaining membrane integrity, synthesizing hormones, and forming bile acids, but its excess is detrimental. Maintaining cholesterol balance depends on coordinated synthesis, transport by lipoproteins, and elimination. This article examines cholesterol transport pathways, the role of HDL in reverse cholesterol transport, and the diseases associated with dysregulated cholesterol metabolism.

High-Density Lipoproteins (HDLs)

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is the fourth major class of lipoproteins in mammals and is synthesized in the liver and small intestine as small, protein-rich particles containing minimal cholesterol and no cholesteryl esters. Unlike other lipoproteins that primarily deliver cholesterol to tissues, HDL plays a central role in maintaining cholesterol balance by removing excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues. This cholesterol is then transported back to the liver, where it can be reutilized or eliminated.

Reverse cholesterol transport

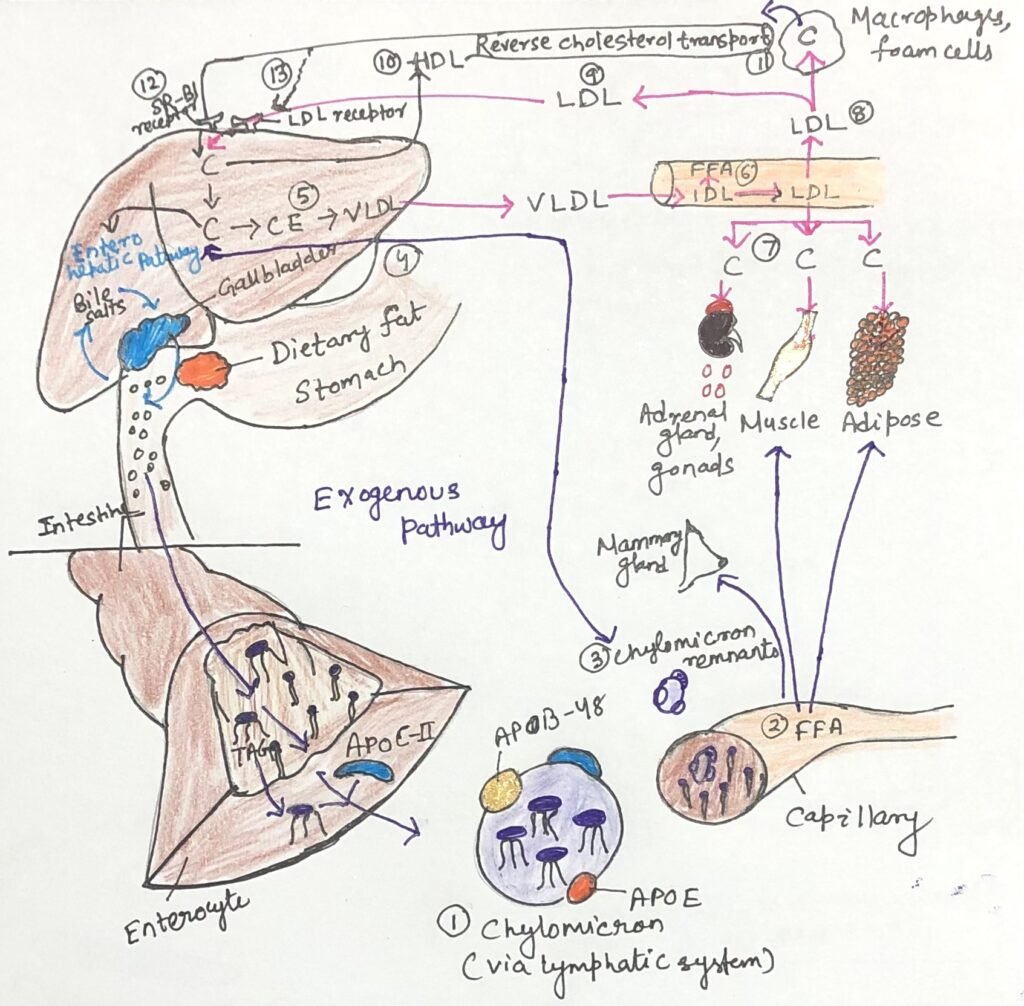

In the article, cholesterol transport and lipoprotein Metabolism, cholesterol transport was described primarily through the exogenous and endogenous pathways (Figure 1). These pathways involve the delivery of dietary cholesterol to tissues via chylomicrons, and liver-derived cholesterol is distributed through VLDL and LDL. While these pathways ensure the supply of cholesterol to peripheral tissues, they also create the risk of cholesterol accumulation. Reverse cholesterol transport, mediated by high-density lipoprotein (HDL), serves as a complementary and protective pathway that counterbalances LDL-mediated cholesterol delivery. In this process, HDL removes excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues and macrophages and transports it back to the liver.

The cholesterol returned by HDL may enter the enterohepatic pathway, where it is converted into bile acids or secreted into bile for elimination through the intestine. Thus, HDL links peripheral cholesterol removal to hepatic processing and intestinal excretion, integrating reverse cholesterol transport with both the exogenous and enterohepatic pathways to maintain overall cholesterol homeostasis.

Reverse Cholesterol Transport Mediated by HDL

High-density lipoproteins (HDLs) are composed mainly of apolipoprotein A-I along with smaller amounts of other apolipoproteins and the enzyme lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT). LCAT catalyzes the esterification of free cholesterol using phosphatidylcholine as a substrate, generating cholesteryl esters. On the surface of nascent, disk-shaped HDL particles, LCAT converts cholesterol acquired from chylomicron and VLDL remnants in the circulation into cholesteryl esters, which accumulate in the particle core and promote the transformation of nascent HDL into a mature, spherical HDL particle.

In addition to accepting cholesterol from lipoprotein remnants, nascent HDL also removes excess cholesterol from cholesterol-rich extrahepatic cells, including macrophages and foam cells. Mature HDL subsequently transports cholesterol back to the liver, where scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) selectively takes it up. This cyclical movement of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver via HDL constitutes the reverse cholesterol transport pathway. In the liver, enzymes located in hepatic peroxisomes convert much of the returned cholesterol into bile acids. The gallbladder stores these bile acids and releases them into the intestine during digestion, after which the intestine reabsorbs most of them and returns them to the liver through the enterohepatic circulation.

Regulation of Cholesterol Homeostasis

Cells maintain cholesterol homeostasis by tightly regulating its synthesis, transport, and removal. Because cholesterol synthesis requires substantial energy and cells cannot degrade excess cholesterol for energy, they carefully coordinate its production with dietary intake and cellular demand. In mammals, intracellular cholesterol levels, cellular energy status, and hormonal signals such as insulin and glucagon actively regulate cholesterol metabolism. Alongside biosynthetic control, HDL-mediated reverse cholesterol transport plays a critical role in preventing cholesterol accumulation in peripheral tissues by facilitating its return to the liver for reutilization or conversion into bile acids. Disruption of these interconnected regulatory mechanisms—whether in synthesis, transport, or clearance leads to cholesterol imbalance and underlies the development of several lipid-related disorders.

Cholesterol Imbalance and Cardiovascular Disease

Animal cells are unable to degrade cholesterol for energy. Therefore, the body must eliminate excess cholesterol either by direct excretion or by converting it into bile acids. When cholesterol synthesis and dietary intake exceed the body’s requirements for membrane formation, steroid hormone production, and bile salt synthesis, cholesterol can accumulate abnormally within the body. Such excess deposition, particularly within blood vessels, leads to atherosclerosis. The condition narrows and obstructs the arteries. Cardiovascular complications arising from atherosclerosis, including coronary artery disease and heart failure, remain a leading cause of mortality in industrialized nations.

Molecular and Cellular Basis of Atherosclerosis

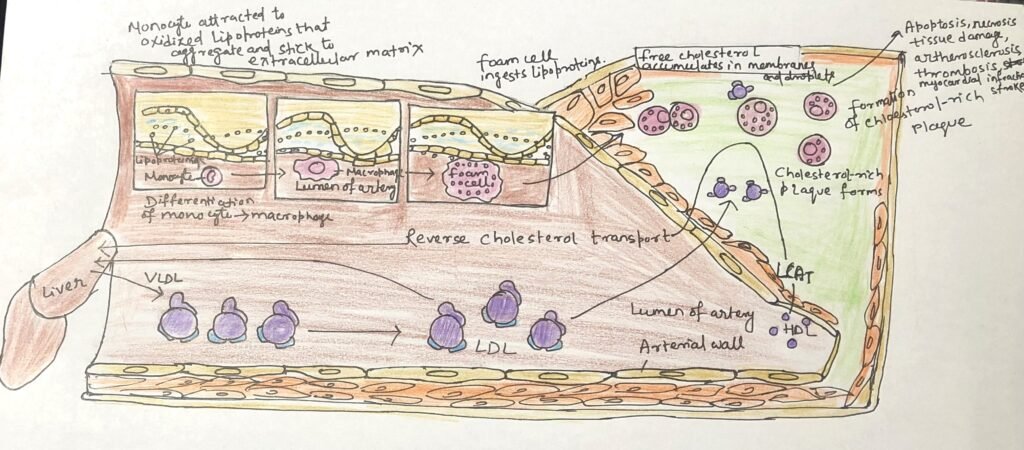

Elevated levels of circulating cholesterol, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL), strongly promote the development of atherosclerosis. In contrast, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels show an inverse relationship with arterial disease, reflecting its protective role in cholesterol removal. Plaque formation begins when LDL particles containing partially oxidized fatty acids adhere to and accumulate within the extracellular matrix of arterial endothelial cells. This accumulation attracts immune cells, particularly monocytes, which migrate into the arterial wall and differentiate into macrophages (Figure 2).

Macrophages engulf oxidized LDL particles and the cholesterol they carry; however, unlike other cells, they lack effective mechanisms to regulate sterol uptake. As cholesteryl esters and free cholesterol progressively accumulate, macrophages transform into lipid-laden foam cells. Excess free cholesterol disrupts membrane integrity, ultimately triggering foam cell apoptosis. Over time, the remnants of dead foam cells, along with extracellular matrix components and smooth muscle–derived scar tissue, form growing atherosclerotic plaques that increasingly narrow arterial lumens. In some cases, plaque rupture and embolization can block blood flow in critical vessels of the heart or brain, resulting in myocardial infarction or stroke.

Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Therapeutic Approaches

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) causes extremely high blood cholesterol levels and triggers the early development of severe atherosclerosis, often beginning in childhood. Individuals with FH have defective LDL receptors, which prevent the normal receptor-mediated uptake of cholesterol from LDL particles. As a result, cholesterol accumulates in the blood, builds up within foam cells, and drives the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Despite elevated serum cholesterol, endogenous cholesterol synthesis continues because extracellular cholesterol cannot enter cells to regulate intracellular production.

HDL-Mediated Reverse Cholesterol Transport from Peripheral Tissues

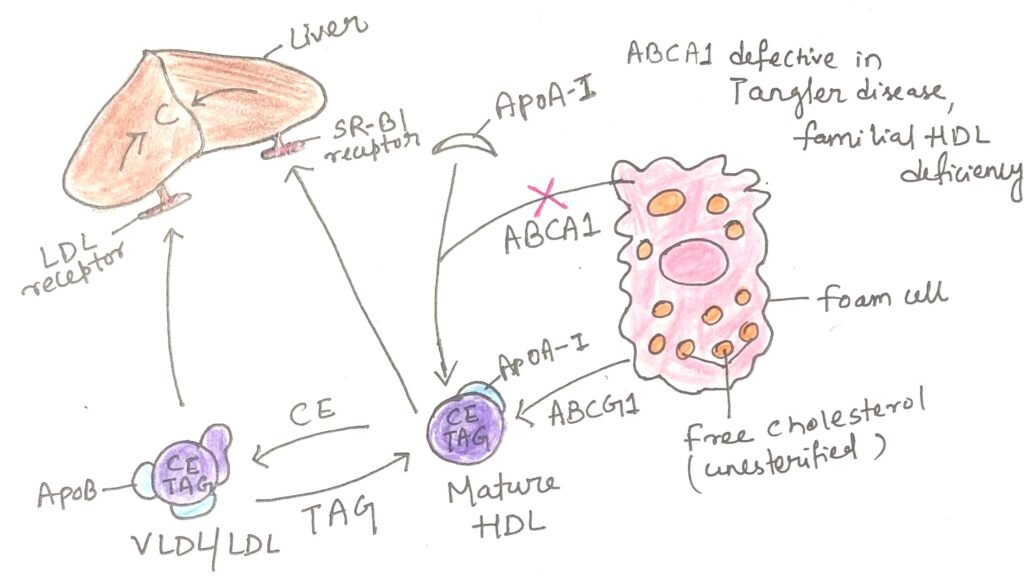

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is central to reverse cholesterol transport, a protective pathway (Figure 3) that limits tissue damage caused by the accumulation of foam cells. Cholesterol-depleted HDL particles collect excess cholesterol from extrahepatic tissues, including foam cells present in early atherosclerotic plaques, and deliver it back to the liver for processing and elimination.

The removal of cholesterol from cells depends on specialized membrane transporters. Among the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family encoded in the human genome, two play key roles in cholesterol efflux. The transporter ABCA1 facilitates the transfer of intracellular cholesterol to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, where lipid-free or lipid-poor apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) binds and accepts the cholesterol for transport to the liver (Figure). A second transporter, ABCG1, interacts with mature HDL particles and promotes further cholesterol efflux from cells. This coordinated process is especially important in clearing cholesterol from foam cells within arterial plaques, thereby reducing cardiovascular disease risk.

Treatment strategies for FH include the use of statins, which reduce cholesterol synthesis and lower serum cholesterol levels. Clinicians most commonly prescribe statins to lower cholesterol levels. While side effects are a consideration with any drug, many effects of statins are actually beneficial. These medications can improve blood flow, enhance the stability of atherosclerotic plaques, reduce platelet aggregation, and decrease vascular inflammation. However, a small number of individuals, particularly those taking statins in combination with other cholesterol-lowering drugs, may experience muscle pain or weakness, which in rare cases can become severe and debilitating.

An alternative approach involves activating Liver X Receptors (LXRs), nuclear transcription factors triggered by oxysterol ligands that coordinate the metabolism of sterols, fatty acids, and glucose. Drugs such as ezetimibe exploit this pathway to help control cholesterol levels and mitigate the risk of cardiovascular complications.

Genetic Disorders Associated with HDL Deficiency

Familial HDL deficiency and Tangier disease cause extremely low levels of circulating HDL due to inherited genetic defects. In Tangier disease, HDL is nearly absent. Both conditions arise from mutations in the ABCA1 transporter. In the absence of functional ABCA1, apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) in cholesterol-poor HDL particles is unable to acquire cholesterol from peripheral cells. As a result, the body rapidly clears and degrades apoA-I and nascent HDL particles from the bloodstream. Although these disorders are uncommon, they provide strong evidence for the essential roles of ABCA1 and related transporters such as ABCG1 in maintaining normal plasma HDL levels and regulating cholesterol homeostasis.

Conclusion

Humans maintain cholesterol homeostasis through a finely balanced network of synthesis, transport, utilization, and excretion pathways. While lipoproteins such as chylomicrons, VLDL, and LDL distribute cholesterol to tissues for structural and metabolic needs, excessive accumulation, particularly through elevated LDL, can drive pathological processes such as atherosclerosis. In contrast, HDL serves a protective function by mediating reverse cholesterol transport, removing excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues and foam cells and returning it to the liver for conversion to bile acids or excretion via the enterohepatic circulation. Genetic disorders affecting cholesterol transporters, such as familial hypercholesterolemia, Tangier disease, and familial HDL deficiency, underscore the critical roles of LDL receptors and ABC transporters in regulating plasma cholesterol levels. Dysregulation of these tightly controlled pathways leads to cardiovascular disease, highlighting the importance of balanced lipoprotein metabolism in maintaining vascular health.

You may also like:

- The Importance of Fat Soluble Vitamins

- Triacylglycerols: Energy Storage, Insulation, and Health Impacts of Partial Hydrogenation

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.