In this article, I briefly describe the types of therapeutic approaches to immune suppression. Therapeutic approaches to immune suppression encompass a broad range of strategies designed to prevent or modulate the host’s immune response against transplanted tissues. These interventions target key cellular and molecular pathways involved in allorecognition, aiming to preserve graft function while minimizing systemic immune compromise.

Immunosuppressive therapies

Immunosuppressive therapy forms the foundation of successful organ transplantation by controlling the body’s natural tendency to attack foreign tissues. Since the immune system is programmed to eliminate anything it perceives as non-self, these medications help dampen that response, allowing the transplanted organ to function and survive. By targeting specific immune cells and signals, immunosuppressive treatments make long-term graft acceptance possible while balancing the need to maintain overall immune protection.

Generalized Immunosuppressive Therapies

Early advances in transplant immunology showed that drugs could effectively suppress immune responses. Research in animal models revealed that certain antimetabolite compounds could reduce immune activity, leading to the development of azathioprine for use in human transplantation. When combined with corticosteroids, this drug significantly improved graft survival, marking a breakthrough in transplant medicine.

Mitotic Inhibitors in Transplantation

Azathioprine is a strong inhibitor of cell division and is commonly used around the time of transplantation to reduce the proliferation of both T and B lymphocytes. Other drugs in this group, such as cyclophosphamide and methotrexate, are sometimes used to control immune cell expansion. These agents are most effective against rapidly dividing cells, making them useful for limiting the immune response, though they may also affect other rapidly growing tissues.

Role of Corticosteroids in Immune Suppression

Clinicians frequently use corticosteroids, such as prednisone and dexamethasone, alongside other immunosuppressive agents. They work by suppressing inflammatory pathways and reducing the production of immune mediators like cytokines, largely by inhibiting key transcription factors involved in immune activation. This combined approach helps prevent graft rejection and improves transplant outcomes.

Advances in Selective Immune Suppression for Transplant Success

The introduction of fungal-derived immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine A, tacrolimus (FK506), and rapamycin, marked a major advance in selective immune regulation. Despite their distinct chemical structures, these agents function similarly by blocking the activation and expansion of resting T cells. They achieve this in part by suppressing the transcription of key molecules required for T-cell activation, including IL-2 and its high-affinity receptor (IL-2Rα). By limiting TH-cell proliferation and cytokine production, these drugs effectively prevent the downstream activation of immune effector mechanisms that drive graft rejection. As a result, they have become essential components of immunosuppressive regimens in organ transplantation, including heart, liver, kidney, and bone marrow grafts.

Specific Immunosuppressive Therapy

The optimal immunosuppressive therapy would act in an antigen-specific manner, suppressing immune responses solely against donor alloantigens while maintaining the host’s ability to defend against other pathogens. Although such precision has not yet been fully achieved, significant progress has been made with the development of more selective immunosuppressive strategies. These approaches primarily utilize monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or soluble ligands designed to bind specific cell-surface molecules involved in immune activation.

Early generations of these antibodies, derived from nonhuman sources, had a major drawback: recipients frequently mounted immune responses against their foreign epitopes, resulting in rapid clearance and reduced therapeutic efficacy. Researchers largely overcame this challenge by developing humanized and chimeric mouse-human mAbs, which offer better compatibility, lower immunogenicity, and improved pharmacokinetics.

Monoclonal Antibody–Based Strategies for Immune Modulation in Transplantation

A wide range of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) has been explored for use in transplantation, and most of them actively deplete specific immune cell subsets or interrupt essential immune-signaling pathways. Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), produced by immunizing animals with human lymphocytes, effectively reduces lymphocyte numbers before transplantation, although it causes notable adverse effects. A more targeted approach employs OKT3, a monoclonal antibody against the CD3 component of the T-cell receptor complex. OKT3 causes rapid depletion of circulating mature T cells, primarily through Fc-mediated clearance by phagocytes. Coupling these antibodies with cytotoxic agents like diphtheria toxin further enhances their lethality, because cells internalize the toxin–antibody complexes and undergo cell death.

Another strategy utilizes basiliximab, an antibody directed against CD25, the high-affinity IL-2 receptor. Because CD25 expression is limited to activated T cells, this therapy selectively inhibits the proliferation of T cells responding to donor alloantigens. However, a potential limitation is that regulatory T cells (TREGs), which contribute to tolerance, also express CD25. Additional advances include the use of anti-CD20 antibodies to eliminate mature B cells and thereby suppress antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). In bone marrow transplantation, clinicians use mAbs targeting T-cell–specific markers to purge immunocompetent donor T cells and reduce the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).

Cytokines are key mediators of allograft rejection, making them attractive targets for selective immunosuppression. Experimental studies in animal models have evaluated monoclonal antibodies directed against cytokines strongly associated with transplant rejection, including TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2. In mice, anti–anti-TNF-α antibodies extend the survival of bone marrow grafts and significantly lower the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).

Inhibition of T-Cell Co-stimulation in Transplant Immunotherapy

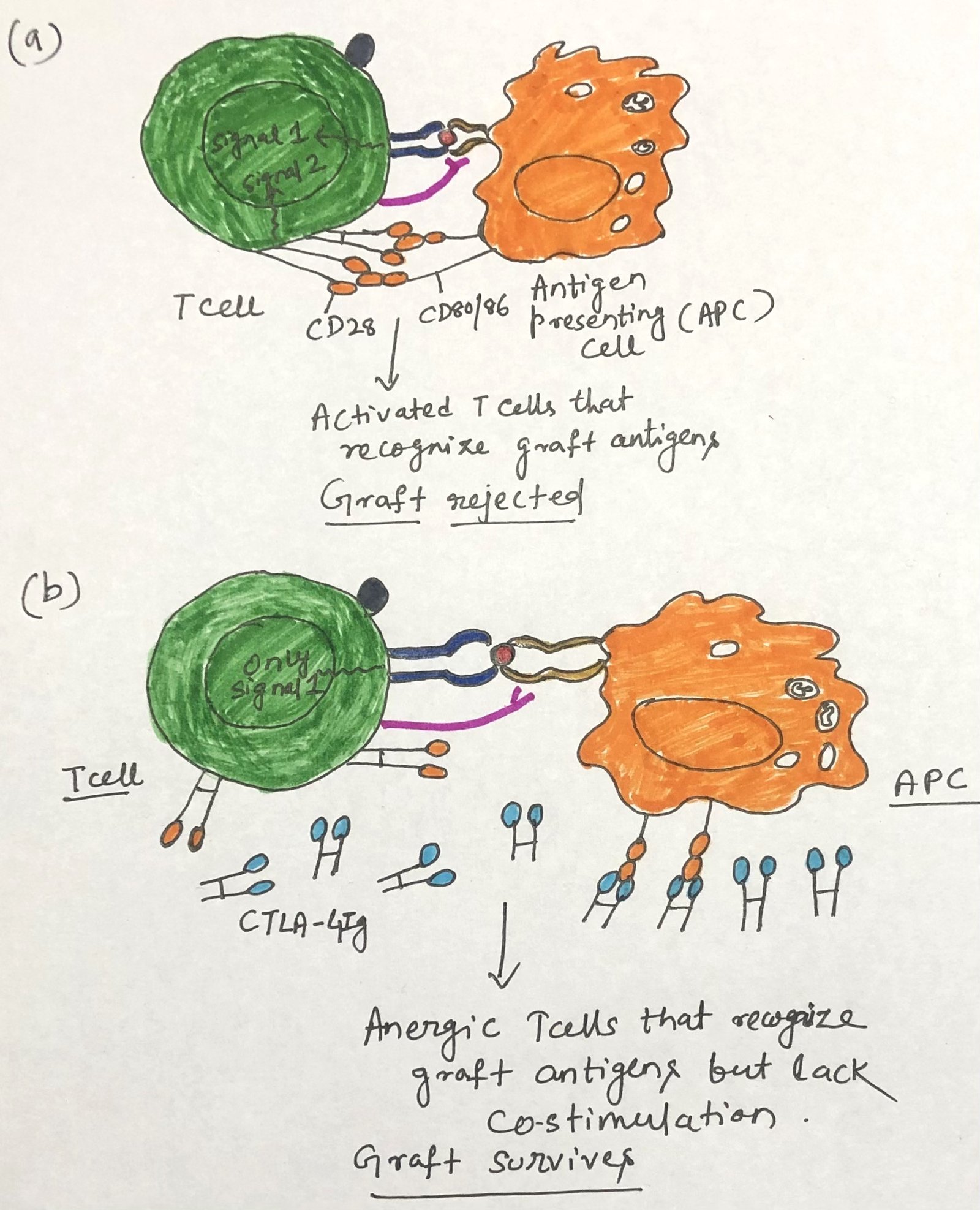

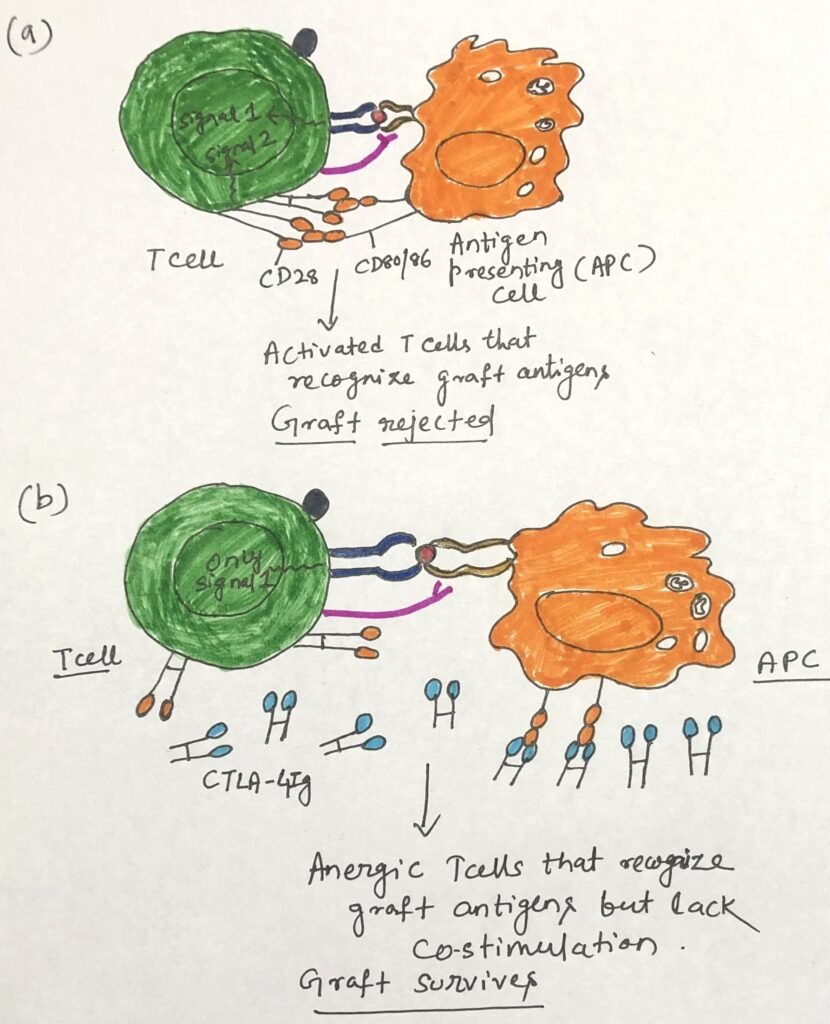

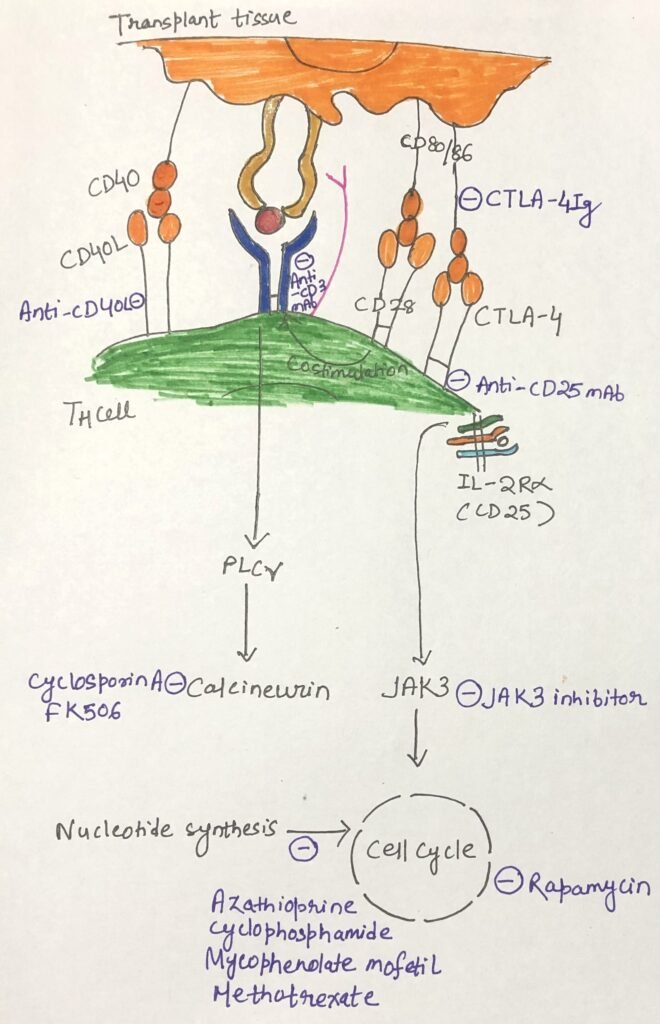

TH-cell activation requires a costimulatory signal in addition to the signal mediated by the TCR. The interaction between CD80/86 on the same membrane of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and the CD28 or CTLA-4 molecule on T cells provides one such signal (Figure 1a). Without this costimulatory signal, antigen-activated T cells become anergic (Figure 1b). CD28 appears on both resting and activated T cells, whereas CTLA-4 appears only on activated T cells and binds CD80/86 with a 20-fold higher affinity.

Scientists have demonstrated prolonged graft survival by blocking CD80/86 signaling in mice using a soluble fusion protein consisting of the extracellular domain of CTLA-4 fused to human IgG1 heavy chain. Belatacept (Nulojix) induces anergy in T cells directed against the graft and has received FDA approval for preventing organ rejection in adult kidney transplant patients. Figure 2 outlines a range of clinical strategies used to suppress transplant rejection and shows the specific points in the immune response where each one acts.

Conclusion

The success of transplantation depends on overcoming the recipient’s immune response while preserving the graft’s long-term function. Although certain anatomical sites naturally limit immune access and promote graft survival, most allografts require deliberate immunosuppressive strategies to prevent rejection. Advances in immunology have clarified the roles of regulatory T cells, cytokine networks, and costimulatory pathways, leading to progressively more targeted approaches.

Therapies have evolved from broad mitotic inhibitors and corticosteroids to highly specific agents such as calcineurin inhibitors, rapamycin, humanized monoclonal antibodies, and costimulatory blockers like belatacept. Each acts at defined checkpoints in the immune response, improving graft survival and reducing adverse effects. Emerging methods—including induction of donor-specific TREG cells and physical immune-shielding of grafted tissues—offer promising routes toward more selective tolerance.

Overall, the field is steadily moving from generalized immune suppression to precise, mechanism-based modulation, bringing transplantation closer to the goal of achieving durable, antigen-specific tolerance.

You may also like:

- Pre-Transplantation Tests for Organ Transplantation

- The Basics of Organ Transplantation

- Induction of Immune Tolerance in Organ Transplantation

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.