In this article, I briefly describe the normal flora of the intestinal tract. It explains how the intestinal flora develops, changes, and functions throughout life. Various factors, including diet, stress, illness, and antibiotics, can alter this delicate balance. It also highlights the role of beneficial microbes and the potential health impacts of microbial by-products, emphasizing the importance of a stable gut microbiota for overall well-being.

Normal Flora

The human body is home to a diverse community of microorganisms collectively known as the normal flora or microbiota. These include bacteria, fungi, and protozoa that inhabit various regions such as the skin, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and other mucosal surfaces. Among these, bacteria constitute the majority of the normal flora, while fungi and protozoa are present in much smaller numbers. Viruses, although they may persist in the body without causing disease, are generally not considered part of the normal flora. The establishment of this microbial community begins immediately after birth, when the body’s external and internal surfaces are first exposed to the surrounding environment.

Intestinal Tract

The stomach continuously receives many bacteria from the mouth, yet in a healthy state, its fluid usually contains fewer than 10 bacteria per milliliter. This is due to the bactericidal action of hydrochloric acid present in gastric secretions. The few microbes that survive are mostly lactobacilli and yeasts, such as Candida species. After food intake, bacterial numbers rise temporarily, then decrease quickly as gastric juice is secreted and the stomach’s pH becomes more acidic.

Small Intestine

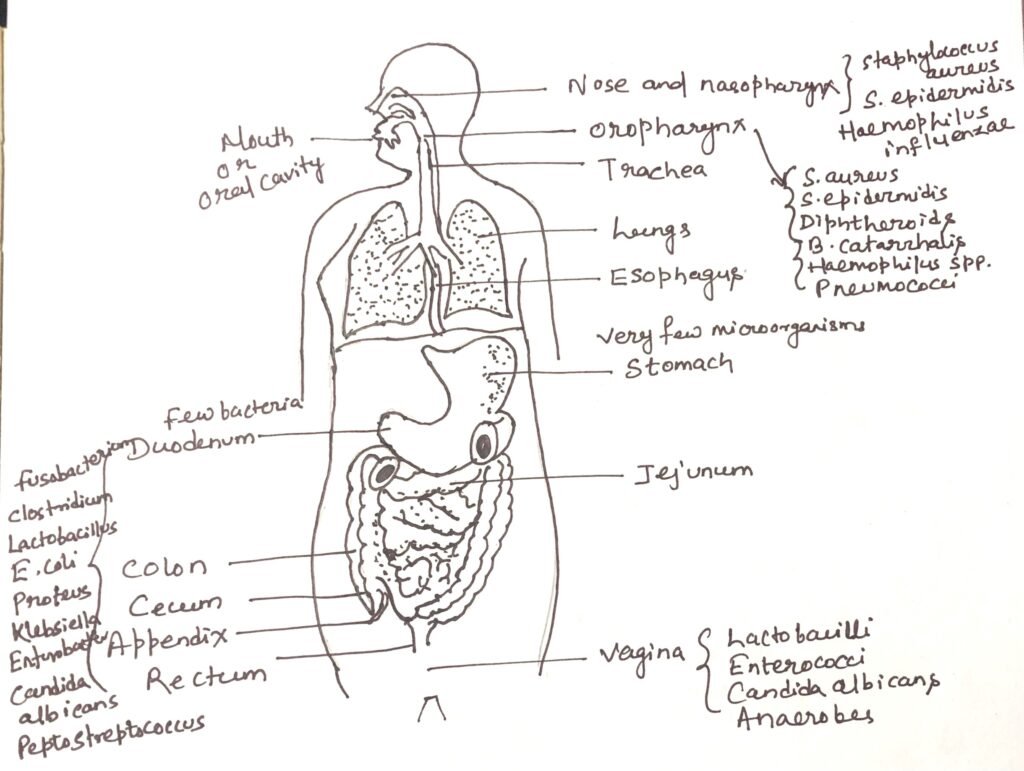

The upper part of the small intestine, known as the duodenum (Figure 1), contains only a small number of bacteria, most of which are Gram-positive cocci and bacilli. The section between the duodenum and the ileum is called the jejunum. Here, species such as enterococci, lactobacilli, and diphtheroids are occasionally present, along with the yeast Candida albicans. Toward the lower end of the small intestine, the microbial population becomes more similar to that of the large intestine, with a significant increase in anaerobic bacteria and members of the Enterobacteriaceae family.

Microbial Composition and Dynamics of the Large Intestine

The colon, or large intestine, harbors the largest and most diverse microbial population in the human body (Figure 1). More than 300 bacterial species have been identified from human feces, and it is estimated that an adult excretes approximately 3 × 10¹³ bacteria each day.

Several natural processes help remove microorganisms from the large intestine. These include peristalsis, which continuously moves intestinal contents; shedding of epithelial cells, to which bacteria often adhere; and the action of mucus, which assists in the mechanical clearance of microbes. Unlike in the respiratory tract, intestinal mucus forms a discontinuous, mesh-like layer. As intestinal contents move, microorganisms attach to this mucus, which then rolls into small masses that are expelled from the body along with feces.

The intestinal flora is dominated by anaerobic bacteria, which outnumber facultatively anaerobic species by about 300 to 1. Among the anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli, common genera include Bacteroides (e.g., B. fragilis, B. melaninogenicus, B. oralis) and Fusobacterium. The Gram-positive anaerobic bacilli are mainly represented by Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, and Lactobacillus.

Facultatively anaerobic bacteria present in the intestine belong to genera such as Escherichia, Proteus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter, while Peptostreptococcus species are also frequently found. Additionally, the yeast Candida albicans is a common resident of the large intestine.

Commensal and Pathogenic Protozoa of the Intestine

Certain protozoa exist in the human intestine as harmless commensals, thriving in anaerobic conditions by feeding on resident bacteria. For example, the flagellated protozoan Trichomonas hominis inhabits the cecal region of the intestinal tract. Similarly, several amoebae belonging to the genera Entamoeba, Endolimax, and Iodamoeba are common commensals of the colon. However, Entamoeba histolytica is unique in that it can behave both as a commensal organism and a pathogen. When pathogenic, it penetrates the intestinal mucosa and may spread to other organs, leading to amoebic dysentery.

Development of Intestinal Flora in Infants

In breast-fed infants, the intestinal microbiota is dominated by Gram-positive Bifidobacterium species. In contrast, bottle-fed infants primarily harbor Gram-positive Lactobacillus species. As solid foods are introduced and the diet transitions to an adult pattern, the intestinal flora shifts toward a Gram-negative community, mainly composed of Bacteroides species.

Factors influencing the intestinal Normal Flora

Many elements can influence the makeup of the normal gut microbiota. Emotional stress, altitude-related pressure changes, and starvation can all shift the microbial balance. Diarrhea also causes major changes because the rapid movement of intestinal contents disrupts the existing flora. Antibiotic use further alters this balance by destroying susceptible bacteria, allowing resistant strains to become dominant. Other influences include dietary habits, bile acids entering the duodenum from the gallbladder, and antibiotics that are naturally secreted into the intestinal tract.

Role of Lactobacillus in Restoring Intestinal Balance

Extended use of certain antibiotics can destroy many of the normal gut microorganisms, allowing antibiotic-resistant species to overgrow. This imbalance may lead to digestive issues such as constipation or diarrhea. In some cases, taking Lactobacillus acidophilus orally helps relieve these problems. Successful establishment of these lactobacilli in the intestine requires consuming them in large numbers along with an appropriate carbohydrate, such as lactose, that is poorly absorbed by the body but readily utilized by the bacteria.

Mutagen Production by Intestinal Microflora and Its Relation with Colon Cancer

In 1977, researchers identified a mutagenic substance in the feces of healthy individuals. Since diet is strongly associated with colon cancer risk, this finding drew significant attention. By 1982, studies showed that certain normal intestinal microbes can convert a precursor compound in feces into this mutagen. However, it remains unclear whether this precursor originates from the person’s diet, from their own metabolic processes, or from other microorganisms within the gut.

Conclusion

The human intestinal tract contains a diverse and constantly changing community of microorganisms shaped by age, diet, health, and environment. In infants, bifidobacteria or lactobacilli dominate, while in adults, anaerobes, especially Bacteroides, are most common. This microbiota continually adjusts to physiological changes. Factors such as stress, altitude, starvation, diarrhea, and antibiotic use can disturb this balance, sometimes allowing resistant organisms to overgrow and cause digestive problems. Beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus can help restore stability when consumed in sufficient amounts with suitable nutrients. Research also shows that some gut microbes can produce mutagenic compounds, linking them to conditions like colon cancer. Overall, the normal intestinal flora plays a crucial role in maintaining digestive health and supporting overall well-being.

You may also like:

- Normal Flora of the Skin, Eye, and Respiratory Tract

- Soil Microbial Flora

- Common intestinal diseases

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.