In this article, I provide a brief overview of the major pathways involved in cholesterol transport and lipoprotein metabolism, which regulate lipid distribution and homeostasis in humans. Cholesterol plays a crucial role in numerous biological processes, yet its movement within the body requires specialized transport systems. Lipoproteins enable the circulation of cholesterol and other lipids through the bloodstream.

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is an essential lipid molecule present in many animals, including humans. Although it plays crucial roles in cellular structure and function, cholesterol is not required in the mammalian diet because all cells are capable of synthesizing it from simple metabolic precursors. Cholesterol is a 27-carbon compound, indicating a highly complex biosynthetic pathway. Remarkably, all of its carbon atoms are derived from a single precursor, acetate.

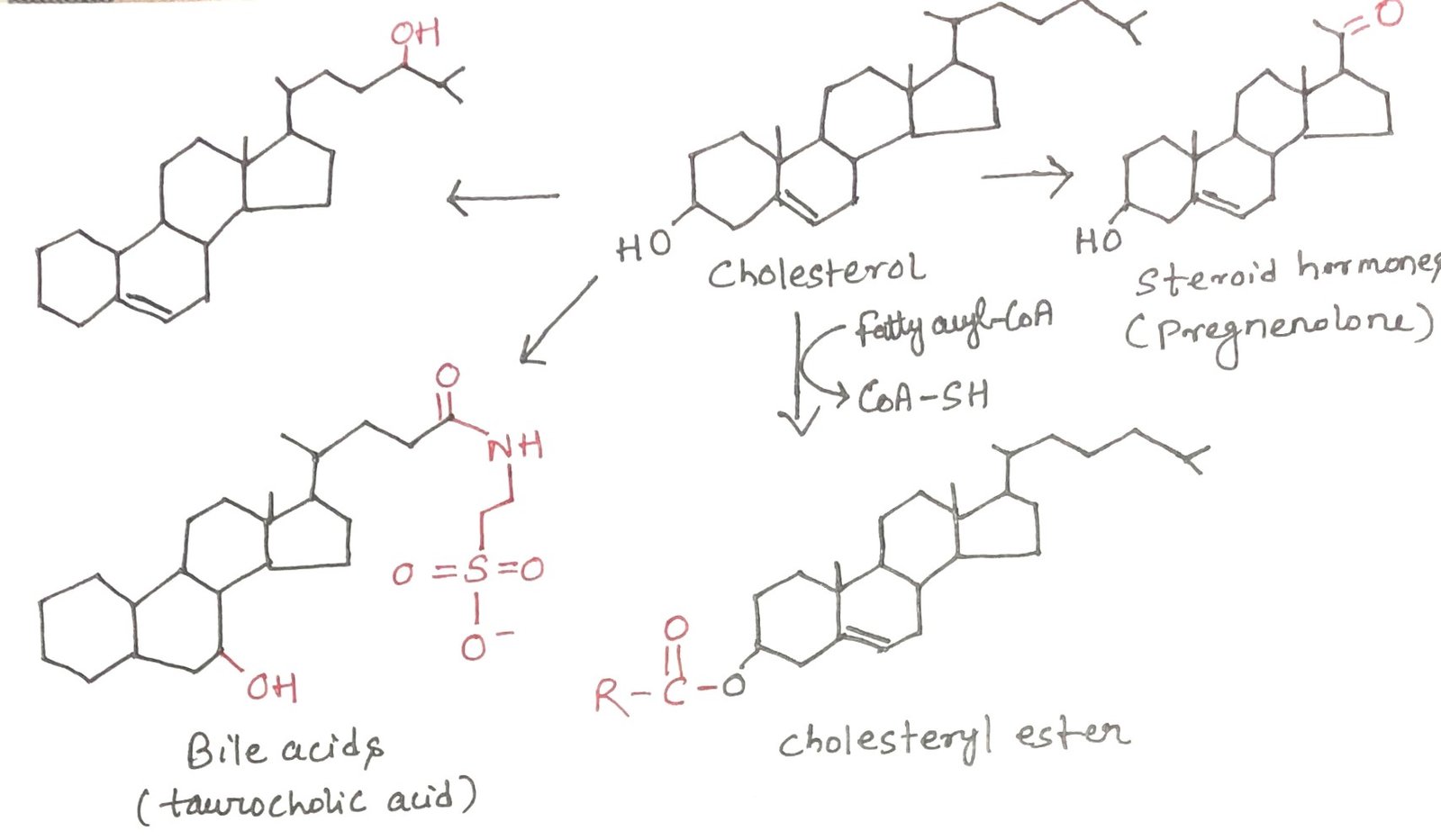

Cholesterol biosynthesis occurs from acetyl-CoA through three major stages. In the first stage, three acetate units condense to form a six-carbon intermediate known as mevalonate, which is subsequently converted into activated isoprene units. In the second stage, six five-carbon isoprene units polymerize to produce the 30-carbon linear molecule squalene. Finally, squalene undergoes cyclization to form the characteristic four-ring steroid nucleus, followed by a series of enzymatic modifications that ultimately yield cholesterol (Figure 1).

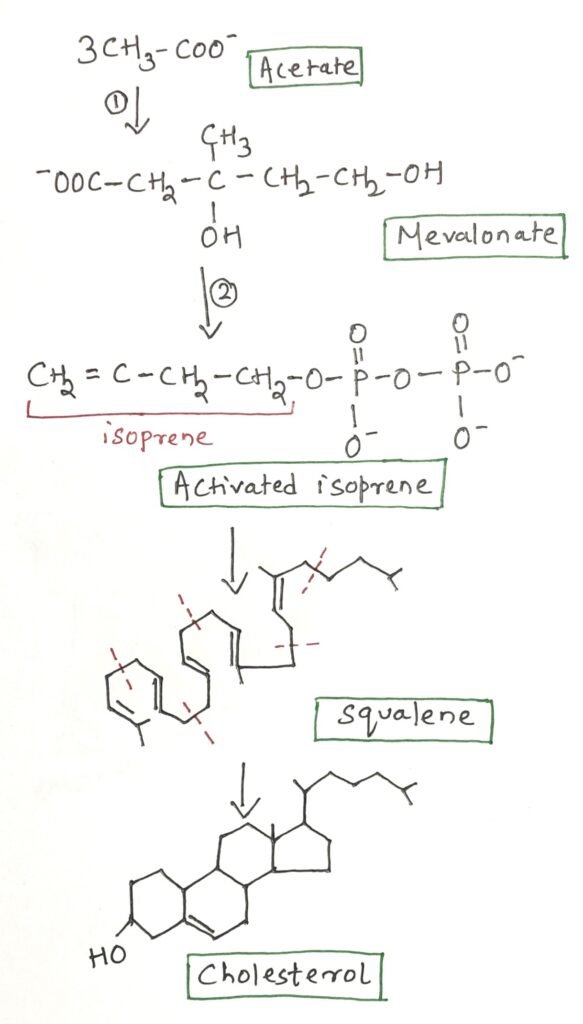

Export of Cholesterol as Bile Acids and Cholesteryl Esters

In vertebrates, the liver is the primary site of cholesterol biosynthesis. Only a small portion of the cholesterol produced in hepatocytes is utilized locally for membrane formation. The majority is transported out of the liver in one of three major forms: bile acids, free cholesterol secreted into bile, or cholesteryl esters (Figure 2).

Bile Acids

Bile acids are the main constituents of bile, a digestive fluid synthesized by the liver, stored in the gallbladder, and released into the small intestine during digestion. These molecules are amphipathic derivatives of cholesterol that function as biological detergents. By emulsifying dietary fats, bile acids break large lipid droplets into smaller micelles, thereby increasing the surface area available for the action of pancreatic lipases and enhancing fat digestion and absorption.

Cholesteryl Esters

Cholesteryl esters are synthesized in the liver by the enzyme acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT). This enzyme transfers a fatty acyl group from coenzyme A to the hydroxyl group of cholesterol, producing a more hydrophobic esterified form. Esterification prevents cholesterol from being incorporated into cellular membranes. Cholesteryl esters are packaged into lipoprotein particles for transport to peripheral tissues requiring cholesterol, or they are stored within hepatocytes as lipid droplets for future use.

Transport of Cholesterol in Blood Plasma

Cholesterol and cholesteryl esters, similar to triacylglycerols and phospholipids, are largely insoluble in aqueous environments. As a result, they are transported in the bloodstream in the form of plasma lipoproteins. These lipoproteins are large macromolecular complexes composed of specific carrier proteins known as apolipoproteins, along with varying proportions of phospholipids, free cholesterol, cholesteryl esters, and triacylglycerols.

Apolipoproteins associate with lipids to form several distinct classes of lipoprotein particles. These particles are spherical in structure, containing a core of hydrophobic lipids surrounded by a surface layer of amphipathic molecules, where the hydrophilic amino acid side chains of apolipoproteins face the aqueous plasma. In human plasma, at least ten different apolipoproteins have been identified, each differing in molecular size, immunological properties, and specific distribution among lipoprotein classes. These protein components play critical regulatory roles by directing lipoproteins to particular tissues and activating enzymes involved in lipoprotein metabolism.

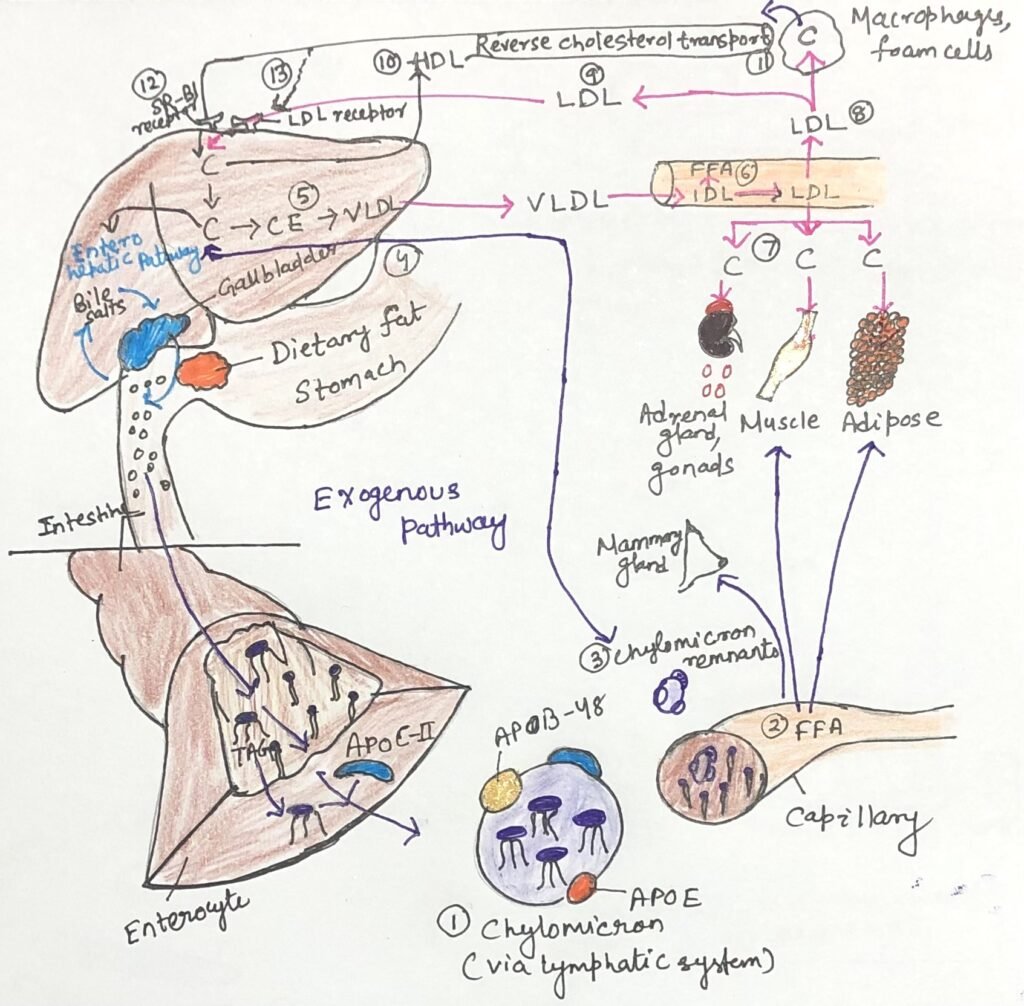

Chylomicrons and VLDL: Transport of Dietary and Endogenous Lipids

Chylomicrons are the largest and least dense class of lipoproteins, characterized by their very high triacylglycerol content. They are formed in the endoplasmic reticulum of enterocytes, the epithelial cells lining the small intestine, from absorbed dietary lipids (Figure 3, step 1). After synthesis, chylomicrons are released into the lymphatic system and subsequently enter the bloodstream through the left subclavian vein. Their major apolipoproteins include apoB-48, apoE, and apoC-II.

ApoC-II plays a key functional role by activating lipoprotein lipase (Figure 3, step 2) located on the capillary walls of adipose tissue, cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, and lactating mammary glands. This enzyme hydrolyzes triacylglycerols within chylomicrons, releasing free fatty acids that are taken up by these tissues for energy production or storage. Following the loss of most of their triacylglycerols, chylomicrons are converted into chylomicron remnants (Figure 3, step 3), which remain enriched in cholesterol and contain apoE and apoB-48. These remnants circulate to the liver (Figure 3, step 4), where apoE binds to specific hepatic receptors, facilitating their uptake by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Within hepatocytes, the remnants are degraded in lysosomes, releasing cholesterol.

When dietary intake supplies more fatty acids and cholesterol than are immediately required for metabolic needs, these excess lipids are converted in the liver into triacylglycerols and cholesteryl esters (Figure 3, step 5). These lipids, along with excess carbohydrates that have been transformed into triacylglycerols, are packaged with specific apolipoproteins into very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). VLDL particles contain apoB-100, apoC-I, apoC-II, apoC-III, and apoE, in addition to triacylglycerols and cholesteryl esters.

Role of VLDL in Lipid Transport and Energy Metabolism

Very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) are synthesized and secreted by the liver and transported through the bloodstream to adipose tissue and muscle. Within the capillaries of these tissues, apolipoprotein C-II activates lipoprotein lipase (Figure 3, step 6), which hydrolyzes the triacylglycerols present in VLDL, releasing free fatty acids.

In adipose tissue, these fatty acids are taken up by adipocytes, re-esterified into triacylglycerols, and stored in intracellular lipid droplets. In contrast, cardiac and skeletal muscle cells primarily oxidize the fatty acids to meet their energy requirements. Under postprandial conditions, when insulin levels are elevated, VLDL mainly functions to transport lipids for storage in adipose tissue. During fasting, however, the fatty acids used for VLDL synthesis in the liver are derived largely from adipose tissue. In this metabolic state, the principal targets of VLDL are the myocytes of the heart and skeletal muscle.

LDL and the Endogenous Pathway of Cholesterol Transport

As triacylglycerols are progressively removed, some very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) are converted into VLDL remnants, also known as intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), which are further processed to form low-density lipoproteins (LDL). LDL particles are enriched in cholesterol and cholesteryl esters and contain apolipoprotein B-100 as their principal protein component. Their primary function is to deliver cholesterol to extrahepatic tissues, including muscle, adrenal glands, and adipose tissue (Figure 3, step 7).

Cells in these tissues express LDL receptors on their plasma membranes that specifically recognize apoB-100, enabling receptor-mediated uptake of LDL and its cholesterol cargo. LDL also supplies cholesterol to macrophages (Figure 3, step 8); excessive uptake by these cells can lead to the formation of lipid-laden foam cells, a key event in atherosclerosis. LDL particles that are not taken up by peripheral tissues return to the liver, where they are internalized through LDL receptors on hepatocytes (Figure 3, step 9).

Within the liver, cholesterol derived from LDL may be incorporated into cellular membranes, converted into bile acids, or re-esterified by acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) and stored in cytosolic lipid droplets. This sequence of events—from VLDL synthesis in the liver to LDL delivery and subsequent hepatic uptake—constitutes the endogenous pathway of cholesterol transport and metabolism. When intracellular cholesterol levels are sufficient, endogenous cholesterol synthesis is downregulated, thereby preventing excessive accumulation of cholesterol within cells.

LDL Receptor–Mediated Uptake of Cholesterol

Each LDL particle circulating in the blood contains apolipoprotein B-100, which is specifically recognized by LDL receptors on the plasma membranes of cells requiring cholesterol. These receptors are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 4, step 1), processed in the Golgi apparatus, and transported to the cell surface, where they bind LDL particles.

The interaction between LDL and its receptor triggers receptor-mediated endocytosis (Figure 4, step 2), enclosing the complex within an endosome (Figure 4, step 3). The receptors are then recycled back to the plasma membrane, allowing repeated rounds of LDL uptake (Figure 4, step 4). The endosome subsequently fuses with a lysosome (Figure 4 step 5), where cholesteryl esters within LDL are hydrolysed, releasing free cholesterol and fatty acids into the cytosol (Figure 4 step 6). The apoB-100 protein component is also degraded to amino acids. This process provides cells with cholesterol while maintaining efficient receptor recycling.

Familial hypercholesterolemia

Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein clarified the molecular pathway responsible for cholesterol transport in the bloodstream and its uptake by cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Their work revealed that individuals affected by the inherited disorder familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) carry mutations in the gene encoding the LDL receptor. These mutations impair the liver and peripheral tissues from efficiently removing LDL from the circulation.

As a consequence of defective LDL receptor function, LDL accumulates in the blood to abnormally high levels. This persistent elevation of circulating LDL significantly increases the risk of developing atherosclerosis, a cardiovascular disease characterized by the formation of cholesterol-rich plaques within arterial walls, leading to vessel narrowing and impaired blood flow.

Niemann Pick type-C (NPC)

Niemann–Pick disease type C (NPC) is a hereditary lipid storage disorder characterized by defective intracellular cholesterol trafficking. In this condition, cholesterol fails to exit the lysosomes and consequently accumulates within the lysosomes of organs such as the liver, brain, and lungs, often leading to severe pathology and early mortality.

NPC arises from mutations in either the NPC1 or NPC2 gene, both of which are essential for transporting cholesterol from the lysosome to the cytosol, where it can undergo further metabolism. The NPC1 gene encodes a transmembrane protein located in the lysosomal membrane, whereas NPC2 encodes a soluble lysosomal protein. Together, these two proteins function cooperatively to facilitate the movement of cholesterol out of the lysosome and into the cytosol for proper cellular processing.

High-Density Lipoproteins in Cholesterol Balance

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is the fourth major class of lipoproteins in mammals and is synthesized primarily in the liver and small intestine. It is initially released as a small, dense, protein-rich particle containing very little cholesterol and no cholesteryl esters. HDL is composed mainly of apolipoprotein A-I, along with smaller amounts of other apolipoproteins. As HDL circulates in the bloodstream, it plays a crucial role in reverse cholesterol transport by accepting excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues and macrophages. This cholesterol is subsequently esterified and transported back to the liver, where it can be reutilized or eliminated. Through this process, HDL contributes to maintaining cholesterol homeostasis and protects against cholesterol accumulation in tissues.

Conclusion

Cholesterol metabolism in humans is a highly coordinated process involving its synthesis in the liver, conversion into bile acids and cholesteryl esters, and transport through the bloodstream by specialized lipoproteins. Dietary lipids are delivered to tissues via chylomicrons, while endogenously synthesized lipids are exported from the liver as VLDL and subsequently processed into LDL, the primary carrier of cholesterol to extrahepatic tissues. Cellular uptake of LDL occurs through receptor-mediated endocytosis, ensuring a regulated supply of cholesterol for membrane synthesis, steroid hormone production, and other essential functions. Disruptions in these pathways, as seen in genetic disorders such as familial hypercholesterolemia and Niemann–Pick disease type C, result in abnormal cholesterol accumulation and severe pathological consequences. Together, these mechanisms highlight the importance of tightly regulated cholesterol transport and intracellular trafficking in maintaining lipid homeostasis and preventing disease.

You may also like:

- The Importance of Fat Soluble Vitamins

- Triacylglycerols: Energy Storage, Insulation, and Health Impacts of Partial Hydrogenation

- Proteins Facilitate the Transbilayer Movement of a Lipid Molecule

I, Swagatika Sahu (author of this website), have done my master’s in Biotechnology. I have around fourteen years of experience in writing and believe that writing is a great way to share knowledge. I hope the articles on the website will help users in enhancing their intellect in Biotechnology.